The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of the 110 Cartridge Format

By 2009, 110 was dead. But in 2011, Lomography brought it back!

Part 1: Drop-in cartridge film formats: Prioritizing user convenience.

By Jason Schneider

In the palmy days of Eastman Kodak Co. when film was still king and digital cameras (the first one was developed by Kodak scientist Steve Sasson in December 1975) were but a distant blip on the horizon, Kodak introduced a new film format about once every 10 years. The objectives: to “refresh” the market by selling a new breed of cameras and film that offered clear operational advantages to consumers, thereby helping to maintain Kodak’s leadership position in the photographic space, and to increase its profit margins

For Kodak it began with the 126 cartridge , the precursor of 110.

A classic example of this winning strategy were the 126 Kodak Instamatic cameras and film cartridges that were launched in 1963. The 126-cartridge trademarked by Kodak as “Kodapak,” was designed to address widespread consumer complaints about the complications entailed in loading and unloading roll film and 35mm cameras. The use of an integrated, one-piece, drop-in cassette providing both the film supply and take-up functions eliminated the need to attach a film leader to the take-up spool—and the necessity of rewinding 35mm film before unloading.

The 126 Instamatic Cassette simply drops into the camera, and because it’s asymmetrical it can’t be loaded incorrectly. Once the camera back is closed, the camera is ready to wind and shoot, greatly simplifying the picture taking experience, and creating potential new markets for Kodak. Kodak Instamatic and other 126 cameras have a window on the back showing the film details, and a small hole revealing the frame number printed on the paper backing. Another advantage: even if the cassette is inadvertently removed in mid-roll, only the current frame will be light struck; the rest of the film is protected inside the cartridge.

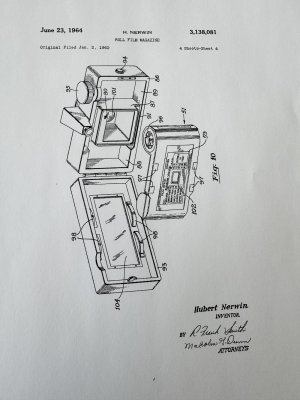

Patent Illistration of 126 Instamatic camera and cartridge, filed on Jan. 2, 1962 by inventor Hubert Nerwin.

The inventor of the 126 Instamatic cartridge was Hubert Nerwin, who was granted U.S. patent no. 3,138,091 on June 23, 1964 that was subsequently assigned to Eastman Kodak. Nerwin, a world-renowned engineer, had been chief designer at Zeiss Ikon during the 1930s. Prior to relocating in the U.S.in 1948 as part of Operation Paperclip (a secret U.S. Intelligence program that relocated over 1.600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians to the U.S. after World War II) Nerwin had designed the formidable Contax II and III rangefinder 35s, the exquisitely complex Contaflex “system TLR” and contributed to design of the new simplified, more reliable shutter used in the postwar Contax IIa and IIIa. His design for the 126 cartridge also incorporated the first widely used mechanical film-speed sensing mechanisms using notches on the cassette for automatically keying in speeds of ASA 64, 80, 125, and 160. However not all Instamatic cameras took advantage of this feature.

Details of 126 Instamatic cartridge patented by Hubert Nerwin and assigned to Kodak.

126 film is 35mm wide and has a single perforation per frame. The image size is nominally 26 x26mm, though the actual film area is 28 x 28mm, masked to approximately 26-1/2 x 26-1/2mm. Thus the 126 format is just over 80% of the area of a standard 24 x 36mm frame of 35mm film. The film has pre-exposed borders and exposure numbers, and the dimensions of the cartridge limit the maximum number of frames to 24. Though the cast majority of Instamatic cameras (by Kodak and others) were relatively simple snapshot cameras, there was a niche market of more sophisticated models including the Kodak Instamatic 700 of 1965 (which had a coupled rangefinder, a selenium metering system, and 38mm f/2,8 Kodak Ektanar lens), and the beautiful German-made Kodak Instamatic 500 of 1963-1966, which had a 38mm f/2.8 Schneider Xenar lens, a Compur shutter with speeds if 1/30 to 1/500 sec, a built-in Gossen selenium meter with indicator in the viewfinder, and a bright frame viewfinder with parallax compensation markings. Another landmark Instamatic: The 1968-1974 Kodak Instamatic Reflex, a system SLR made by Kodak AG Germany that had Retina-compatible lenses including a 45mm f/2.8 Schneider Xenar, a 50mm f/1.9 Schneider Xenon and other lenses from 28mm to 200mm, a Compur Electronic shutter with speeds from 20-1/500 sec, and a non-TTL CdS cell autoexposure system with readouts in the finder.

Kodachrome in an Instamatic? Yep. And here's a 126 cartridge of Kodachrome 64 to prove it!.

It has long been rumored that 126 cartridges have a film flatness problem and that Pocket Instamatic110 cartridges are much better in that respect. However, this has little to do with the design of the cartridges, both which are conceptually quite similar. It’s simply that any wider a paper-backed roll film is (in this case 26 or 28mm vs. 13mm) is inherently less likely to maintain perfect film flatness at the film plane. Bottom line: both 126 and 110 cartridges are capable of excellent results, but you’re more common to get an occasional “soft frame” with 126, especially if you often shoot at the widest apertures.

Kodak AG Germany Instamatic 500, one of the coolest Instamatics ever.

Prophetically, the 126 format was officially discontinued by Kodak on the very last day if the 20th century, December 31,1999. It was rendered functionally obsolete by the introduction of the smaller, more portable 110 Pocket Instamatic format in 1972, and the proliferation of so-called “auto everything” 35mm cameras beginning with the Canon AF 35M “Sure Shot” of 1979, which featured easy loading, auto wind, auto rewind, and active near-IR autofocus, and was widely copied by camera manufacturers worldwide. Whatever their imperfections, the original Kodak Instamatics, their myriad successors, and the 126 cartridge itself were perhaps the greatest marketing success of all time, with over 75 million units sold through 1976 by Kodak alone!

Most Advanced Kodak Instamatic? We pick this Kodak Retina Reflex S by Kodak AG Germany.

The 110 Pocket Instamatic cartridge: Ultraminiature for the masses!

Prototype 110 cartridges created by Hubert Nerwin, inventor of the 126 Instamatic cartridge.

Kodak introduced the 110 or Pocket Instamatic format 9 years after bringing forth the larger 126 cameras and cartridges in 1963. 110 cassettes contain paper backed 16mm wide film with one perforation per frame, and have a pin next to the film gate (aka film aperture) to control film advance and spacing. Like 126, 110 film is pre-exposed with a border and frame number between the frames, and the paper backing is imprinted with frame numbers that can be seen in a small window in the back of the cartridge. The frame numbers and film details on the cartridge label are visible through the larger window in the camera’s film chamber door. Rewinding is not required, and only one frame will be lost if the camera is inadvertently opened before all frames are exposed.

Kodacolor Gold 110 Pocket Instamaric 24-exposure cartridge.

The 110 Pocket Instamatic cartridge differs in its details but is conceptually the same as the 126 Instamatic cartridge. It provides a format size of 13 x17mm (0.51 x o,67 inches). The smaller size 110 negatives or slides could yield high quality enlargements up to 11 x 14 inches due to “improvements in film technology” and the slim, pocketable form factor of most Pocket Instamatic and other 110 cameras more closely matches that of older 16mm niche market ultraminiature cameras. Since neither Kodak nor anyone else applied for a patent on the 110 cartridge we cannot be sure who “invented” it, but a likely candidate is (surprise, surprise!) Hubert Nerwin, who devised the 126 regular Instamatic cartridge! Nerwin’s son generously donated a couple of has dad’s prototype 110 cartridges (shown here) to the George Eastman Museum in Rochester NY, so we can be sure Hubert Nerwin worked on the development project. Evidently Kodak decided not to expend the time and resources needed to secure a patent, assuming competitors would use it as is, thus benefitting Kodak 110 film sales. It’s also worth noting that the smaller film cartridge required less silver halide material, thus providing a greater ROI (return on investment) for Kodak.

When Kodak introduced the 110 cartridge and Kodak Pocket Instamatic cameras in 1972, four films were made available—Kodachrome-X and Ektachrome-X for slides, Kodacolor II for color prints, and Verichrome Pan film for black and white prints. The 16mm film width allowed Kodachrome 110 to be processed using Standard 8mm and existing processing machines for Standard 8mm and 16mm movie film. Along with standard-sized 35mm slide mounts, 110 slide film could also be processed into smaller slides that could be conveniently projected in a Kodak Pocket Carousel or Leica 110 projector. Although the 110 format is most closely associated with low-cost “snapshot” cameras, Canon, Minolta, Pentax, Rollei, Voigtlander, Kodak and others offered sophisticated high-end 110 cameras with excellent multi-element lenses, rangefinder or SLR focusing, and precise electronically controlled exposure systems. We’ll detail about 10 of these in “Part II, The Cameras.” Some writers have asserted that deficiencies in the110 cartridge itself and/or its imprecise positioning in the film plane limited the image quality obtainable with this format, and that 110-format cameras generally yielded inferior results compared to the 16mm subminiature cameras that preceded them. However, none of these claims is true so long as the camera has been focused precisely on the intended subject and the film has been properly exposed and processed. Indeed. the only technical issue that seriously compromised user satisfaction with 110 was substandard processing and printing by some commercial labs, which often resulted in soft prints of mediocre quality, creating an erroneous impression that the culprit was the 110 format itself. Smaller formats do require a greater degree of stewardship on the part of labs, and sadly that was not always forthcoming in the 110 era.

A Century of Cartridge Loading Still Picture Formats: 1904-1996

APS of 1996 cartridge with detailed callouts of features. Status indicators on right.

The abstract of Hubert Nerwin’s U.S. Patent No. 3,138,081 for the 126 Instamatic cartridge, originally filed on Jan. 2, 1962, concludes with a list of relevant U.S. and British patents including two by Walter Zapp dated 1939 and 1940. Zapp, a Baltic German, was born in 1905 in Riga, then part of the Russian Empire, and later the capital of Latvia. Inspired by friends to devise an ultra-portable camera Zapp demonstrated his Minox prototype to representatives of VEF (Valsts Elektrotechniska Fabrika) in 1936 and the “Riga Minox” went into production in Riga at VEF from 1937 to 1943. VEF also received patent protection for Zapp’s inventions in 18 countries.

The original Riga-made Minox had a brass chassis contained in a stainless steel shell, which telescopes to reveal the lens and viewfinder windows, and simultaneously advance the film. It had a parallax-correcting viewfinder, a 15mm f/3.5 Minostigmat triplet lens that manually focused down to 20cm (about 8 inches), and a metal foil focal plane shutter with speeds of ½- sec to 1/1000 sec plus B and T. The shutter was mounted in front of the lens that was protected by a window. This was a very advanced feature set for its day, and the exquisitely minuscule 80mm x 27mm x 16mm Minox quickly became a “must have” item among the cognoscenti.

But the crowning glory of the Riga Minox was its patented one-piece two-chamber metal drop-in cartridge that provided an 8 x 11mm format on 9.2mm-wide roll film, and required no sprocket holes! Instead, the strip of film is rolled up into the supply side of the cartridge with the film leader taped to the spool in the take-up chamber. Minox cartridges for the Riga Minix, the postwar Minox II, III, IIs and B could provide up to 50 exposures. Later Minox models BL, C and onward used 15-, 30-, or 35-exposure cartridges. The last ultraminiature Minox, the TLX, rolled off the production line in September 2014, a remarkably long 77-year run!

The Expo Pocket Watch Camera: The first cartridge loader? Maybe.

Back view of Expo Pocket Watch camera with back removed, film cartridge in place.

Expo drop-in film cassette containing 25 exposures of 17.5mm-wide roll film, each frame measuring 5/8 x 7/8 inches has U.S. patent dated 1904.

Patented in September 1904 (U.S Patent 769,3i9) and invented by Magnus Neill of New York, this ingenious miniature camera in the form of a pocket watch provided instant daylight loading using one-piece drop-in film cassette containing 25 exposures of 17.5mm-wide roll film, each frame measuring 5/8 x 7/8 inches. A spool within the cassette interlocked with the film winding key on the outside of the camera, and a coupled film counter kept track of the exposures. Film spools containing Eastman Kodak N.C. film were priced at 20 cents. These were easily loaded into the cassette, but the system did not fully eliminate into the film loading process. Also, the Expo’s shutter was not self-capping, so you had to place the lens cap, which resembles a watch winding knob, over the lens while cocking the shutter. This fascinating all metal ultraminiature novelty camera was finished in shiny silver, measures 2-1/8 inches in diameter, 7/8 inches thick, and weighs in at a mere 2-3/4 ounces despite its robust construction. Made by the Expo Camera Co. of New York, it was available new until 1939, an amazing 34-year run.

Evidently the New York company ran into financial difficulties at some point prompting Houghton’s Ltd. of London (which had the manufacturing rights) to produce a nearly identical pocket watch camera called (in the longstanding British tradition of horrible puns), the Ticka, which sold fir the grand sum of 8 shillings, 6 pence. An accessory Ticka viewfinder ran 1 shilling 6 pence and a spool of Ticka Ensign film was a mere 10d, (ten pence), Oh happy days!

Currently, a used Expo in good nick will set you back about $150-$300; a Ticka, $365-$525.

Advanced Photo System: Kodak's last gasp attempt to “save” film?

Advanced Photo System (APS) is a single cartridge instant-loading film format optimized for consumer still imaging that was introduced in 1996 and discontinued in 2011. Like prior attempts to replace 35mm film, it used a film cartridge to greatly simplify film loading and unloading. By reducing the maximum image area of the format to 30.2 x 16.7mm, camera size, lens size, and weight could be substantially reduced, and by using newly developed films with finer grain and a flatter base material, image quality could be maintained. The other major innovation of APS which automatically advanced and rewound the film once the cartridge was inserted, was “information exchange,” that is recoding data directly on the film so it could be cropped into a desired aspect ratio and provide photofinishers with exposure data to optimize print quality. Sadly, by the time the ingenious APS system debuted in 1996, the first digital cameras appeared, providing many if the same benefits plus the additional convenience of eliminating the developing process. And by about 2000, it was clear to many that digital imaging was destined to dominate the market in the years to come.

APS contact sheets and cartridge storage box.

In 1991 Canon, Fujifilm, Kodak, Minolta, and Nikon formed a consortium to complete the APS system. Details of initial testing including info on the magnetic stripe information and specs of the 3 APS formats, H (High Definition) 30.2 x16.7mm) Classic (25.1 x 16.7mm), and Panoramic (30.2 x 9.5mm), were released in 1994. The film is on a polyethylene naphthalate (PEN) base and wound on a single spool housed in a plastic cartridge measuring 39mmm (1.5 in.) in length. The basic diagonal is 21mm while the opposite diagonal measures 30mm, including the corner where the film exits. The film slot is protected by a lightproof door and cartridges were available in 40-, 25-, and 15-exposure lengths. APS was officially announced at the Photo Marketing Association (PMA) show in Las Vegas in February 1995. APS cameras were sold by several major manufacturers under proprietary brand names including Advantix (Kodak), Nexia (Fujifilm), Futura (Agfa), Centuria (Konica), ELPH (Canon in the U.S.A.) and Vectis (Minolta).

Despite its benefits APS never really caught on with professional photographer, putting a crimp in the enthusiast market, largely because of the significantly smaller frame size compared to standard full frame 35mm. APS emulsions that did indeed deliver superior sharpness but they soon found their way into 35mm cartridges, eliminating one major APS advantage. Finally, a limited selection of film speeds also contributed to the demise of APS, and color slide film in APS format was unpopular and soon phased out. In January 2004, Kodak announced that it was ceasing APS camera production only 8 years after the system was introduced—a sad end to an ingenious system that may not have been too little, but was definitely too late.

By 2009, 110 was dead. But in 2011, Lomography brought it back!

Part 1: Drop-in cartridge film formats: Prioritizing user convenience.

By Jason Schneider

In the palmy days of Eastman Kodak Co. when film was still king and digital cameras (the first one was developed by Kodak scientist Steve Sasson in December 1975) were but a distant blip on the horizon, Kodak introduced a new film format about once every 10 years. The objectives: to “refresh” the market by selling a new breed of cameras and film that offered clear operational advantages to consumers, thereby helping to maintain Kodak’s leadership position in the photographic space, and to increase its profit margins

For Kodak it began with the 126 cartridge , the precursor of 110.

A classic example of this winning strategy were the 126 Kodak Instamatic cameras and film cartridges that were launched in 1963. The 126-cartridge trademarked by Kodak as “Kodapak,” was designed to address widespread consumer complaints about the complications entailed in loading and unloading roll film and 35mm cameras. The use of an integrated, one-piece, drop-in cassette providing both the film supply and take-up functions eliminated the need to attach a film leader to the take-up spool—and the necessity of rewinding 35mm film before unloading.

The 126 Instamatic Cassette simply drops into the camera, and because it’s asymmetrical it can’t be loaded incorrectly. Once the camera back is closed, the camera is ready to wind and shoot, greatly simplifying the picture taking experience, and creating potential new markets for Kodak. Kodak Instamatic and other 126 cameras have a window on the back showing the film details, and a small hole revealing the frame number printed on the paper backing. Another advantage: even if the cassette is inadvertently removed in mid-roll, only the current frame will be light struck; the rest of the film is protected inside the cartridge.

Patent Illistration of 126 Instamatic camera and cartridge, filed on Jan. 2, 1962 by inventor Hubert Nerwin.

The inventor of the 126 Instamatic cartridge was Hubert Nerwin, who was granted U.S. patent no. 3,138,091 on June 23, 1964 that was subsequently assigned to Eastman Kodak. Nerwin, a world-renowned engineer, had been chief designer at Zeiss Ikon during the 1930s. Prior to relocating in the U.S.in 1948 as part of Operation Paperclip (a secret U.S. Intelligence program that relocated over 1.600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians to the U.S. after World War II) Nerwin had designed the formidable Contax II and III rangefinder 35s, the exquisitely complex Contaflex “system TLR” and contributed to design of the new simplified, more reliable shutter used in the postwar Contax IIa and IIIa. His design for the 126 cartridge also incorporated the first widely used mechanical film-speed sensing mechanisms using notches on the cassette for automatically keying in speeds of ASA 64, 80, 125, and 160. However not all Instamatic cameras took advantage of this feature.

Details of 126 Instamatic cartridge patented by Hubert Nerwin and assigned to Kodak.

126 film is 35mm wide and has a single perforation per frame. The image size is nominally 26 x26mm, though the actual film area is 28 x 28mm, masked to approximately 26-1/2 x 26-1/2mm. Thus the 126 format is just over 80% of the area of a standard 24 x 36mm frame of 35mm film. The film has pre-exposed borders and exposure numbers, and the dimensions of the cartridge limit the maximum number of frames to 24. Though the cast majority of Instamatic cameras (by Kodak and others) were relatively simple snapshot cameras, there was a niche market of more sophisticated models including the Kodak Instamatic 700 of 1965 (which had a coupled rangefinder, a selenium metering system, and 38mm f/2,8 Kodak Ektanar lens), and the beautiful German-made Kodak Instamatic 500 of 1963-1966, which had a 38mm f/2.8 Schneider Xenar lens, a Compur shutter with speeds if 1/30 to 1/500 sec, a built-in Gossen selenium meter with indicator in the viewfinder, and a bright frame viewfinder with parallax compensation markings. Another landmark Instamatic: The 1968-1974 Kodak Instamatic Reflex, a system SLR made by Kodak AG Germany that had Retina-compatible lenses including a 45mm f/2.8 Schneider Xenar, a 50mm f/1.9 Schneider Xenon and other lenses from 28mm to 200mm, a Compur Electronic shutter with speeds from 20-1/500 sec, and a non-TTL CdS cell autoexposure system with readouts in the finder.

Kodachrome in an Instamatic? Yep. And here's a 126 cartridge of Kodachrome 64 to prove it!.

It has long been rumored that 126 cartridges have a film flatness problem and that Pocket Instamatic110 cartridges are much better in that respect. However, this has little to do with the design of the cartridges, both which are conceptually quite similar. It’s simply that any wider a paper-backed roll film is (in this case 26 or 28mm vs. 13mm) is inherently less likely to maintain perfect film flatness at the film plane. Bottom line: both 126 and 110 cartridges are capable of excellent results, but you’re more common to get an occasional “soft frame” with 126, especially if you often shoot at the widest apertures.

Kodak AG Germany Instamatic 500, one of the coolest Instamatics ever.

Prophetically, the 126 format was officially discontinued by Kodak on the very last day if the 20th century, December 31,1999. It was rendered functionally obsolete by the introduction of the smaller, more portable 110 Pocket Instamatic format in 1972, and the proliferation of so-called “auto everything” 35mm cameras beginning with the Canon AF 35M “Sure Shot” of 1979, which featured easy loading, auto wind, auto rewind, and active near-IR autofocus, and was widely copied by camera manufacturers worldwide. Whatever their imperfections, the original Kodak Instamatics, their myriad successors, and the 126 cartridge itself were perhaps the greatest marketing success of all time, with over 75 million units sold through 1976 by Kodak alone!

Most Advanced Kodak Instamatic? We pick this Kodak Retina Reflex S by Kodak AG Germany.

The 110 Pocket Instamatic cartridge: Ultraminiature for the masses!

Prototype 110 cartridges created by Hubert Nerwin, inventor of the 126 Instamatic cartridge.

Kodak introduced the 110 or Pocket Instamatic format 9 years after bringing forth the larger 126 cameras and cartridges in 1963. 110 cassettes contain paper backed 16mm wide film with one perforation per frame, and have a pin next to the film gate (aka film aperture) to control film advance and spacing. Like 126, 110 film is pre-exposed with a border and frame number between the frames, and the paper backing is imprinted with frame numbers that can be seen in a small window in the back of the cartridge. The frame numbers and film details on the cartridge label are visible through the larger window in the camera’s film chamber door. Rewinding is not required, and only one frame will be lost if the camera is inadvertently opened before all frames are exposed.

Kodacolor Gold 110 Pocket Instamaric 24-exposure cartridge.

The 110 Pocket Instamatic cartridge differs in its details but is conceptually the same as the 126 Instamatic cartridge. It provides a format size of 13 x17mm (0.51 x o,67 inches). The smaller size 110 negatives or slides could yield high quality enlargements up to 11 x 14 inches due to “improvements in film technology” and the slim, pocketable form factor of most Pocket Instamatic and other 110 cameras more closely matches that of older 16mm niche market ultraminiature cameras. Since neither Kodak nor anyone else applied for a patent on the 110 cartridge we cannot be sure who “invented” it, but a likely candidate is (surprise, surprise!) Hubert Nerwin, who devised the 126 regular Instamatic cartridge! Nerwin’s son generously donated a couple of has dad’s prototype 110 cartridges (shown here) to the George Eastman Museum in Rochester NY, so we can be sure Hubert Nerwin worked on the development project. Evidently Kodak decided not to expend the time and resources needed to secure a patent, assuming competitors would use it as is, thus benefitting Kodak 110 film sales. It’s also worth noting that the smaller film cartridge required less silver halide material, thus providing a greater ROI (return on investment) for Kodak.

When Kodak introduced the 110 cartridge and Kodak Pocket Instamatic cameras in 1972, four films were made available—Kodachrome-X and Ektachrome-X for slides, Kodacolor II for color prints, and Verichrome Pan film for black and white prints. The 16mm film width allowed Kodachrome 110 to be processed using Standard 8mm and existing processing machines for Standard 8mm and 16mm movie film. Along with standard-sized 35mm slide mounts, 110 slide film could also be processed into smaller slides that could be conveniently projected in a Kodak Pocket Carousel or Leica 110 projector. Although the 110 format is most closely associated with low-cost “snapshot” cameras, Canon, Minolta, Pentax, Rollei, Voigtlander, Kodak and others offered sophisticated high-end 110 cameras with excellent multi-element lenses, rangefinder or SLR focusing, and precise electronically controlled exposure systems. We’ll detail about 10 of these in “Part II, The Cameras.” Some writers have asserted that deficiencies in the110 cartridge itself and/or its imprecise positioning in the film plane limited the image quality obtainable with this format, and that 110-format cameras generally yielded inferior results compared to the 16mm subminiature cameras that preceded them. However, none of these claims is true so long as the camera has been focused precisely on the intended subject and the film has been properly exposed and processed. Indeed. the only technical issue that seriously compromised user satisfaction with 110 was substandard processing and printing by some commercial labs, which often resulted in soft prints of mediocre quality, creating an erroneous impression that the culprit was the 110 format itself. Smaller formats do require a greater degree of stewardship on the part of labs, and sadly that was not always forthcoming in the 110 era.

A Century of Cartridge Loading Still Picture Formats: 1904-1996

APS of 1996 cartridge with detailed callouts of features. Status indicators on right.

The abstract of Hubert Nerwin’s U.S. Patent No. 3,138,081 for the 126 Instamatic cartridge, originally filed on Jan. 2, 1962, concludes with a list of relevant U.S. and British patents including two by Walter Zapp dated 1939 and 1940. Zapp, a Baltic German, was born in 1905 in Riga, then part of the Russian Empire, and later the capital of Latvia. Inspired by friends to devise an ultra-portable camera Zapp demonstrated his Minox prototype to representatives of VEF (Valsts Elektrotechniska Fabrika) in 1936 and the “Riga Minox” went into production in Riga at VEF from 1937 to 1943. VEF also received patent protection for Zapp’s inventions in 18 countries.

The original Riga-made Minox had a brass chassis contained in a stainless steel shell, which telescopes to reveal the lens and viewfinder windows, and simultaneously advance the film. It had a parallax-correcting viewfinder, a 15mm f/3.5 Minostigmat triplet lens that manually focused down to 20cm (about 8 inches), and a metal foil focal plane shutter with speeds of ½- sec to 1/1000 sec plus B and T. The shutter was mounted in front of the lens that was protected by a window. This was a very advanced feature set for its day, and the exquisitely minuscule 80mm x 27mm x 16mm Minox quickly became a “must have” item among the cognoscenti.

But the crowning glory of the Riga Minox was its patented one-piece two-chamber metal drop-in cartridge that provided an 8 x 11mm format on 9.2mm-wide roll film, and required no sprocket holes! Instead, the strip of film is rolled up into the supply side of the cartridge with the film leader taped to the spool in the take-up chamber. Minox cartridges for the Riga Minix, the postwar Minox II, III, IIs and B could provide up to 50 exposures. Later Minox models BL, C and onward used 15-, 30-, or 35-exposure cartridges. The last ultraminiature Minox, the TLX, rolled off the production line in September 2014, a remarkably long 77-year run!

The Expo Pocket Watch Camera: The first cartridge loader? Maybe.

Back view of Expo Pocket Watch camera with back removed, film cartridge in place.

Expo drop-in film cassette containing 25 exposures of 17.5mm-wide roll film, each frame measuring 5/8 x 7/8 inches has U.S. patent dated 1904.

Patented in September 1904 (U.S Patent 769,3i9) and invented by Magnus Neill of New York, this ingenious miniature camera in the form of a pocket watch provided instant daylight loading using one-piece drop-in film cassette containing 25 exposures of 17.5mm-wide roll film, each frame measuring 5/8 x 7/8 inches. A spool within the cassette interlocked with the film winding key on the outside of the camera, and a coupled film counter kept track of the exposures. Film spools containing Eastman Kodak N.C. film were priced at 20 cents. These were easily loaded into the cassette, but the system did not fully eliminate into the film loading process. Also, the Expo’s shutter was not self-capping, so you had to place the lens cap, which resembles a watch winding knob, over the lens while cocking the shutter. This fascinating all metal ultraminiature novelty camera was finished in shiny silver, measures 2-1/8 inches in diameter, 7/8 inches thick, and weighs in at a mere 2-3/4 ounces despite its robust construction. Made by the Expo Camera Co. of New York, it was available new until 1939, an amazing 34-year run.

Evidently the New York company ran into financial difficulties at some point prompting Houghton’s Ltd. of London (which had the manufacturing rights) to produce a nearly identical pocket watch camera called (in the longstanding British tradition of horrible puns), the Ticka, which sold fir the grand sum of 8 shillings, 6 pence. An accessory Ticka viewfinder ran 1 shilling 6 pence and a spool of Ticka Ensign film was a mere 10d, (ten pence), Oh happy days!

Currently, a used Expo in good nick will set you back about $150-$300; a Ticka, $365-$525.

Advanced Photo System: Kodak's last gasp attempt to “save” film?

Advanced Photo System (APS) is a single cartridge instant-loading film format optimized for consumer still imaging that was introduced in 1996 and discontinued in 2011. Like prior attempts to replace 35mm film, it used a film cartridge to greatly simplify film loading and unloading. By reducing the maximum image area of the format to 30.2 x 16.7mm, camera size, lens size, and weight could be substantially reduced, and by using newly developed films with finer grain and a flatter base material, image quality could be maintained. The other major innovation of APS which automatically advanced and rewound the film once the cartridge was inserted, was “information exchange,” that is recoding data directly on the film so it could be cropped into a desired aspect ratio and provide photofinishers with exposure data to optimize print quality. Sadly, by the time the ingenious APS system debuted in 1996, the first digital cameras appeared, providing many if the same benefits plus the additional convenience of eliminating the developing process. And by about 2000, it was clear to many that digital imaging was destined to dominate the market in the years to come.

APS contact sheets and cartridge storage box.

In 1991 Canon, Fujifilm, Kodak, Minolta, and Nikon formed a consortium to complete the APS system. Details of initial testing including info on the magnetic stripe information and specs of the 3 APS formats, H (High Definition) 30.2 x16.7mm) Classic (25.1 x 16.7mm), and Panoramic (30.2 x 9.5mm), were released in 1994. The film is on a polyethylene naphthalate (PEN) base and wound on a single spool housed in a plastic cartridge measuring 39mmm (1.5 in.) in length. The basic diagonal is 21mm while the opposite diagonal measures 30mm, including the corner where the film exits. The film slot is protected by a lightproof door and cartridges were available in 40-, 25-, and 15-exposure lengths. APS was officially announced at the Photo Marketing Association (PMA) show in Las Vegas in February 1995. APS cameras were sold by several major manufacturers under proprietary brand names including Advantix (Kodak), Nexia (Fujifilm), Futura (Agfa), Centuria (Konica), ELPH (Canon in the U.S.A.) and Vectis (Minolta).

Despite its benefits APS never really caught on with professional photographer, putting a crimp in the enthusiast market, largely because of the significantly smaller frame size compared to standard full frame 35mm. APS emulsions that did indeed deliver superior sharpness but they soon found their way into 35mm cartridges, eliminating one major APS advantage. Finally, a limited selection of film speeds also contributed to the demise of APS, and color slide film in APS format was unpopular and soon phased out. In January 2004, Kodak announced that it was ceasing APS camera production only 8 years after the system was introduced—a sad end to an ingenious system that may not have been too little, but was definitely too late.

Attachments

Last edited: