Coldkennels

Barnack-toting Brit.

So my Leningrad finally arrived, and while it has slight (hopefully fixable) flaws in the form of a missing RF calibration screw and slow speeds all running at the same speed, it's otherwise functional. And so I've been sat around for the last few hours considering its existence; you don't see much written about it, so I thought I'd perhaps share my experiences.

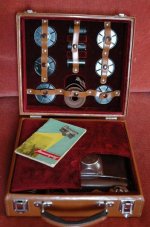

GOMZ Leningrad (1958) by Mark Waldron, on Flickr

(NOT my photo. I don't have a digital camera, hence the lack of images in this big wall of text that follows)

One of the foremost things I read about it before it arrived was it it was big, brick-like, heavy and recoiled like a small cannon every time the spring advance goes off. Now that I finally have it in my hands, I'd like to debunk that... sort of. Because obviously, it ain't no M3. At 94mm x 144mm x 38mm, it's got more in common with the oft-derided M5 than the classic M shape. (For comparison, an M5 comes in at 84x150x36, and the M3 is 77x138x33.5. The extra 10mm height of the Leningrad is almost entirely that huge winding knob.) But that's hardly fair; it's like comparing a speedboat to a pedalo and complaining that it's so much bigger. It's certainly much smaller than the only other camera I have lying around with a motordrive capability (Chinon CM3; 118x141x72) and a lot lighter (740g vs. 890g).

Numbers and statistics aside, it feels good in the hand. The curves on the front form quite satisfying grips, especially on the right hand, which can really get a good, firm hold on what is actually quite a subtle ridge. The kick is somewhat powerful, but not as much as expected; besides, it is delayed until you let go of the shutter release, so if you need a slower exposure, you can hold the camera stable until the curtain has definitely finished its travel.

While I'm on the subject, the shutter mechanism is impressive. It's shockingly fast, although I don't know how much it will slow down when it's pulling a film along. It certainly beats my Chinon's battery-driven motorwinder by a long way, although it won't be anywhere near as fast as a modern professional motordrive. But when you consider it's running entirely off spring tension - and was built in 1963! - it's something fantastic to behold. Quite how reliable it really is I don't know. Maybe it'll die within a year of use. But as it stands, it's certainly deserving of some acclaim. The Russians might take some stick for some of their cameras, but they really got it together with this one. And the noise, too... guh-dang, guh-dang, guh-dang. It's not subtle, but it is fun.

The only downside is some of the more eccentric parts of its design; the oversized wind knob can be awkward to turn due to the position of the oversized shutter release, and removal of the back is so odd I had to look it up. One side has a Fed/Zorki style clasp, and the other is a huge ring that unscrews the base+back from the camera. It's not quick, but I assume for some reason it must be necessary. Engaging the rewind mechanism is also a bit strange - you need to push your thumb onto a disc inside aforementioned huge ring and turn it anti-clockwise until it springs out. I've yet to put an entire film through (just a ruined film I use for testing mechanisms), but the rewind doesn't seem as slow as reported. I'll have to see just how long it takes with a 36exp roll.

The real star of the show, however, is the rangefinder. I've never seen anything like it. It's not a standard ghost-image spot; instead, the rangefinder "spot" is a solid part of the viewfinder, and you have to find and join vertical lines that dissect the boundary between the RF and VF panes. It's not very RF-like - more like a split-prism SLR finder. This design may seem weird, but it actually allows the VF to be brighter and clearer than many cameras. But where it really shines is that as you focus both the RF and the VF images move - in opposition to each other, of course. This is where the claims of parallax correction come from; the framelines (50/85/135 - black, clear, and nice and unobtrusive) remain still while the actual view changes, allowing the limits of the VF to act as a parallax-corrected 35mm frame.

And that's not all. The diopter (adjusted by screwing or unscrewing the VF bezel at the back) has more range than any camera I've seen, allowing even me to see clearly without my glasses (I am extremely short sighted, and have never had this option available before). And while standard vertical and horizontal RF adjustment is easy to access, removal of the top (a surprisingly easy job) allows for adjustment and fine-tuning of the RF image's angle via two screws. No further disassembly or fuss needed.

Whether or not the camera will stand the test of time - and whether or not it will be used on a daily basis when fixed - remains to be seen. But I certainly don't think it deserves the bad rep it seems to get on the rare occasion it gets discussed. It's a shame the design became a bit of a dead-end, and was never pursued and developed further. It's a wonderful piece of equipment when you consider what it is. No, it's not as quiet, small and refined as an M3. But they're very different beasts with very different purposes, and the Leningrad fulfils its purpose well - or at least, it seems to.

GOMZ Leningrad (1958) by Mark Waldron, on Flickr

(NOT my photo. I don't have a digital camera, hence the lack of images in this big wall of text that follows)

One of the foremost things I read about it before it arrived was it it was big, brick-like, heavy and recoiled like a small cannon every time the spring advance goes off. Now that I finally have it in my hands, I'd like to debunk that... sort of. Because obviously, it ain't no M3. At 94mm x 144mm x 38mm, it's got more in common with the oft-derided M5 than the classic M shape. (For comparison, an M5 comes in at 84x150x36, and the M3 is 77x138x33.5. The extra 10mm height of the Leningrad is almost entirely that huge winding knob.) But that's hardly fair; it's like comparing a speedboat to a pedalo and complaining that it's so much bigger. It's certainly much smaller than the only other camera I have lying around with a motordrive capability (Chinon CM3; 118x141x72) and a lot lighter (740g vs. 890g).

Numbers and statistics aside, it feels good in the hand. The curves on the front form quite satisfying grips, especially on the right hand, which can really get a good, firm hold on what is actually quite a subtle ridge. The kick is somewhat powerful, but not as much as expected; besides, it is delayed until you let go of the shutter release, so if you need a slower exposure, you can hold the camera stable until the curtain has definitely finished its travel.

While I'm on the subject, the shutter mechanism is impressive. It's shockingly fast, although I don't know how much it will slow down when it's pulling a film along. It certainly beats my Chinon's battery-driven motorwinder by a long way, although it won't be anywhere near as fast as a modern professional motordrive. But when you consider it's running entirely off spring tension - and was built in 1963! - it's something fantastic to behold. Quite how reliable it really is I don't know. Maybe it'll die within a year of use. But as it stands, it's certainly deserving of some acclaim. The Russians might take some stick for some of their cameras, but they really got it together with this one. And the noise, too... guh-dang, guh-dang, guh-dang. It's not subtle, but it is fun.

The only downside is some of the more eccentric parts of its design; the oversized wind knob can be awkward to turn due to the position of the oversized shutter release, and removal of the back is so odd I had to look it up. One side has a Fed/Zorki style clasp, and the other is a huge ring that unscrews the base+back from the camera. It's not quick, but I assume for some reason it must be necessary. Engaging the rewind mechanism is also a bit strange - you need to push your thumb onto a disc inside aforementioned huge ring and turn it anti-clockwise until it springs out. I've yet to put an entire film through (just a ruined film I use for testing mechanisms), but the rewind doesn't seem as slow as reported. I'll have to see just how long it takes with a 36exp roll.

The real star of the show, however, is the rangefinder. I've never seen anything like it. It's not a standard ghost-image spot; instead, the rangefinder "spot" is a solid part of the viewfinder, and you have to find and join vertical lines that dissect the boundary between the RF and VF panes. It's not very RF-like - more like a split-prism SLR finder. This design may seem weird, but it actually allows the VF to be brighter and clearer than many cameras. But where it really shines is that as you focus both the RF and the VF images move - in opposition to each other, of course. This is where the claims of parallax correction come from; the framelines (50/85/135 - black, clear, and nice and unobtrusive) remain still while the actual view changes, allowing the limits of the VF to act as a parallax-corrected 35mm frame.

And that's not all. The diopter (adjusted by screwing or unscrewing the VF bezel at the back) has more range than any camera I've seen, allowing even me to see clearly without my glasses (I am extremely short sighted, and have never had this option available before). And while standard vertical and horizontal RF adjustment is easy to access, removal of the top (a surprisingly easy job) allows for adjustment and fine-tuning of the RF image's angle via two screws. No further disassembly or fuss needed.

Whether or not the camera will stand the test of time - and whether or not it will be used on a daily basis when fixed - remains to be seen. But I certainly don't think it deserves the bad rep it seems to get on the rare occasion it gets discussed. It's a shame the design became a bit of a dead-end, and was never pursued and developed further. It's a wonderful piece of equipment when you consider what it is. No, it's not as quiet, small and refined as an M3. But they're very different beasts with very different purposes, and the Leningrad fulfils its purpose well - or at least, it seems to.