Coupled Rangefinder 35s and their Discontents:

How to get the most out of everybody’s favorite vintage classics.

By Jason Schneider

I bought my first Leica in 1960—a “window display” Leica IIIg with collapsible 50mm f/2.8 Elmar lens at a whopping 10% off the list price—and I haven’t been the same since. Over the ensuing years I’ve acquired and shot with innumerable rangefinder 35s including Barnack and M Leicas, a splendid variety Canons, a few Nikons, and far too many Contaxes, both prewar and postwar. Despite my undying affection for the breed, rangefinder 35s have their peccadillos and it helps to have a clear grasp of their assets, liabilities, and operating characteristics if you expect to get the most out of them. Let’s start by taking a quick trip down memory lane.

The Leica II (Model D) of 1932, a masterpiece of minimalist ingenuity, sired a generation of screw-mount "Barnack" Leicas that ended in 1960.

The first successful rangefinder 35 was the Leica II, Model D, of 1932 (its archrival, the Contax I released in the same year, had a notoriously unreliable shutter). Essentially the Leica II (Model D) was nothing more than a Leica I (Model C) with interchangeable screw mount lenses on the front and a coupled short base, high magnification (1.5x) rangefinder with a separate optical viewfinder shoehorned into a small housing on the top. The genius of the design was coupling the screw mount lenses to the rangefinder by means of a brass cam on the back of each lens that contacts a roller at the end of a spring-loaded arm inboard of the lens mount. Turning the focusing lever (or ring) of a mounted lens controls the position of the moving coincident rangefinder image so that proper focus is achieved when the moving and fixed (circular) images of the rangefinder coincide (are no longer laterally displaced).

Building all this into a camera virtually the same size as the original “miniature” Leica A was a stunning achievement, and it endured (with various tweaks and modifications) until 1954, when the landmark Leica M3 was announced, and lingered until 1960 when the last screw mount Leica IIIg rolled off the production line. All screw-mount Leicas have reasonably well-defined, very clear circular rangefinder patches, but they’re optimized for superimposed image (coincident) focusing and don’t lend themselves to using the inherently more accurate split-image focusing method. All have less convenient separate viewfinders, and all but the Leica IIIg have small fixed 50mm viewfinders that necessitate using a separate shoe mount accessory viewfinder when shooting with lenses other than 50mm.

Enter the Leica M3: Pioneering the greatest range/viewfinder of all.

The Leica M3 1954 was widely hailed as the finest interchangeable-lens 35mm rangefinder camera ever made, the most advanced practical rangefinder 35 of its day, and the first new-from-the-ground-up Leica in nearly 40 years. The most significant advances in the M3 are a magnificent long base (68.5mm) nearly life-size (0.91X) combined range/viewfinder with true projected, parallax-compensating, auto-indexing frame lines for 50mm, 90mm, and 135mm lenses, the M-type bayonet mount, a two-stroke film-advance lever (later modified to provide single-stroke operation), and a hinged back section to facilitate cleaning, shutter checking, and film alignment. A translucent light-collecting window in between the rangefinder and viewfinder windows provides illumination for the bright, crisp white finder frame lines, and a frame line-selector lever below the front viewfinder window lets you previsualize the effect of mounting other lenses. But merely enumerating its outstanding features hardly does justice to this exquisitely refined machine. The integration of its various components is brilliant. It’s rubberized, 1-1/1000 sec plus B, horizontal travel cloth focal plane shutter is whisper quiet. Its contours mold seamlessly to your hands, and its shutter release, wind lever, and focusing mount operate with an uncanny silky precision. Within a few years, leading Japanese manufacturers, notably Nikon and Canon, produced splendid rivals to the Leica M3 with multi-frame range/viewfinders (see section below) and much more, but none ever equaled, much less surpassed the Leica in terms of overall excellence of design, particularly its superb range/viewfinder, which is yet to be natched by any full frame analog or digital rangefinder camera terms of focusing ease and precision. Perhaps the greatest tribute to the Leica M3 (aside from the legacy of memorable images it has captured) is the fact that it still endures. The current Leica MP and M6 are really nothing more than upgraded M3’s with additional finder frames and built in TTL metering, and the late, lamented M7 is basically an upgraded M3 with built-in autoexposure. And of course, all former and current digital Leica M’s culminating in the present top-of-the-line M11 are built upon the concept and features the M3 set forth nearly 70 years ago.

The Leica M3 of 1954 was a game changer that transformed the interchangeable lens rangefinder 35. I still lives in every analog and digital M.

The Leica M3, and its illustrious stable mates the M2 and M4 are all great (and now rather pricey) user collectibles selling in the $1,500 range in chrome (body only) in clean working condition (prices vary widely so check before pulling the trigger). The single-stroke M3 of the mid-60’s, with more rugged, durable wind and shutter mechanisms, a larger exit pupil for enhanced finder brightness, and serial number above 1,100,000, is especially prized (and more expensive), and early two-stroke models in average condition are more affordable.

Competing with the Leica M? No contest!

To say that the Leica M3 created a sensation and shocked the engineers at Canon, Nikon, and Zeiss when it officially debuted at Photokina 1954 is an understatement. Indeed, the Leica’s competitors were literally blown into the weeds—and they knew it. The top Canon at the time was the bottom loading screw mount Canon IVSB (marketed in the U.S. as the IVS2), which had a tiny range/viewfinder with three magnification settings but no viewfinder frame lines. Nikon offered the Nikon S, which weighs a ton, has a well-executed but dinky range/viewfinder, and a non-standard 24x34mm format. In response to the M3 Nikon brought forth the Nikon S2 in 1955, the first Japanese camera with a film wind lever, rewind crank, and a life-size 1:1 range/viewfinder with a fixed reflected 50 mm frame line—a lovely camera but no match for the mighty M3. Zeiss-Ikon brought forth the Contax IIa/IIIa in 1950, basically a pared down, lighter, slightly smaller, much more reliable versions of the prewar Contax II and III. Like their forbears they had removable backs, a superb line of Contax bayonet mount lenses, and a high quality but smallish range/viewfinder with no frame lines. Sadly (and perhaps wisely) this was to be the final iteration of the classic rangefinder Contax, as Zeiss declined to enter the “rangefinder finder frame line wars” that took place in the mid to late ‘50s among Leica, Nikon, and Canon. By 1959 when the game-changing Nikon F SLR was introduced, Leica had tacitly emerged victorious, although Nikon technically produced a few multi-frame successors to the 1957 Nikon SP in the ‘60s. and Canon soldiered on with the 5-frame-line 7sZ until late 1968.

Nikon S2 of 1955 was Nikon's response to the all-conquering Leica M3. It's a beautiful camera with great features, but not in the same league.

Nikon SP of 1957-1960 want head to head with the Leica M's. It had more finder frame lines, but it never really challenged the M3,M2, and M4.

The glorious Canon 7sZ of 1968, last of the classic rangefinder Canons, has a built in CdS meter and an excellent multi-frame range/viewfinder.

What makes the Leica M range/viewfinder so special?

As the accompanying range/viewfinder diagram taken from Kisselbach’s excellent “The Leica Book” from the 1950s shows, the path of the light passing through the front rangefinder window passes through a solid double deflecting glass prism and is projected through a “telescopic element” coupled to the lens focusing system and into the viewfinder. The field frame illuminated by the central translucent window lies in precisely the same plane. The field frame and rangefinder images (rays) are simultaneously reflected by a beam-splitter into the viewfinder eyepiece where they are joined by the ray coming from the viewfinder, thereby producing a double image of the sighted object. By moving the focusing ring or tab of the lens, these images move closer together or further apart, and when the lens is focused correctly, they merge into a single image.

'50s brochure on the Leica M3 extols the virtues if its range/viewfinder with an excellent schematic showing how it works. Those were the days!

The focusing accuracy of this system is extremely high because the rangefinder patch is so clearly delineated that it’s possible to focus using the traditional coincident (superimposed image) method and also to use the areas above and below the patch to visually form, in effect, a split image rangefinder, that lets you focus by “reconstructing” a broken vertical or oblique line running through the viewfinder images and the rangefinder patch. In addition, the entire projected frame line moves laterally and vertically as the lens is focused to various distances, automatically correcting the parallax error that would otherwise exist between the viewfinder and the camera lens. Other multi-frame range/viewfinder systems (notably those in late model Nikon and Canon rangefinder cameras) provide automatic parallax compensation for a range of focal lengths, but none provide auto indexing, which automatically displays the appropriate frames when you mount a lens, and none is optimized for focusing using the split-image focusing method, claimed by experts to be about 5 times more precise than using the superimposed image (coincident) method.

According to the leading Leica repair experts we spoke with, the Leica M range/viewfinder system affords the following unique advantages:

1.The magnification of the rangefinder patch matches the viewing area very precisely.

2.The rangefinder patch is perfectly symmetrical within the frame line in use and remains centered when lenses of different focal lengths are used, and when the lens is focused.

3.Both the central rangefinder patch and the projected frame lines are crisp and sharp and appear at the same plane as you look through the viewfinder. Two thin pieces of metal provide the frame line parallax compensation for all focal lengths.

Other cool and competent range/viewfinder systems

While there’s no standard production range/viewfinder system that surpasses the one built into Leica M cameras, there is a selection of fascinating alternatives, past and present. Not surprisingly, both the Leica/Leitz Minolta CL and the Minolta CLE (both the results of a longstanding collaboration between Leitz and Minolta) are M-mount rangefinder cameras that use a simplified version of the Leica M range/viewfinder system, and the user manuals for both cameras specifically describe the split-image focusing method and recommend using it to achieve greater focusing accuracy. However, neither one provides the same degree of focusing accuracy as a Leica M.

The Minolta CLE was best camera to emerge from the Leitz/Minolta partnership of the '70s, but Leitz never made lenses specifically for it.

The rangefinder base of the CL is 31.5mm and the viewfinder magnification is 0.60x, resulting in a small effective rangefinder base (EBL) of 18.9 mm. This is too short for accurate focusing with lenses longer than 90mm and fast lenses used at full aperture. The Minolta CLE does better, with an actual rangefinder base length of 49.6mm, a viewfinder magnification of 0.58x and an effective base length of 28.9mm. Both cameras display projected parallax compensating frame lines for 40mm, 50mm, and 90mm lenses. An analog Leica or Leitz Minolta CL body in good shape runs about $350 to $700; a clean functional Minolta CLE will set you back $500-$750, body only.

The Zeiss Ikon ZM of 2005 to 2012 (sometimes simply referred to as the Zeiss Ikon) is a handsome and fascinating M-mount rangefinder camera made by Cosina, designed with input from Zeiss, and compatible with M and LTM-mount lenses by Zeiss (or Leica et al). Its excellent range/viewfinder has a magnification of 0.74x, an actual rangefinder base length of 75mm, and an effective base length of 55.5mm, making it useable with a wider variety of lenses than the CL and CLE. It provides projected, auto indexing, parallax compensating frame lines for 28/85mm (simultaneously), 35mm, and 50mm, offers aperture priority autoexposure like the Minolta CLE, and the manual specifically cites and illustrates its split-image focusing capability. The ZM has one flaw which may or may not be fatal depending on your priorities—its rangefinder mechanism is rather delicate and easy to knock out of whack with rough handling or an incidental impact. It may be OK for general use but it's probably not the best choice for banging around on the trail. ZM’s are also not for the faint of wallet; a clean functional example in black or chrome runs $1,200 to $2,000 body only depending on the specifics.

Zeiss Ikon ZM, made by Cosina with input by Zeiss, is one if the nicest non-Leica M-mount 35's but its rangefinder mechanism is delicate .

Pixii: Leave it to the French to come up with an offbeat but workable take on the M-mount digital rangefinder camera. Originally released in 2018, the latest 26MP APS-C sensor version of 2023 has an “interactive viewfinder” and a new 64-bit quad-core ARM Cortex-A55 processor with a dual-core OpenCL 2.O GPU with 768 threads and speeds up to 7G pixels/sec along with dedicated NPU and VPU cores. As a result, the company claims its latest model is the first color camera capable of capturing true monochrome DNGs and highlights the 64-bit processor’s ability to resolve finer details and create smoother transitions. Pixii claims the new camera can process images 10x faster than previous versions, provides three times faster transfer speeds and extends battery life by 25%. The Pixii has no EVF or LCD (other than a small back-mounted Status Indicator LCD) and is designed to display captured images on a paired device such as a smartphone. However, its optical viewfinder includes parallax compensating frame lines for 28mm, 35mm, and 50mm lenses, exposure indicators at the bottom. and a nice crisply defined rangefinder patch in the center, which is used for manually focusing attached lenses in the traditional manner. While not specifically mentioned in the manual both the superimposed image and split image focusing methods are clearly useable with this camera. An advanced an ingenuous niche product, the latest Pixii sells for $2,800.

Latest 2023 version the French made Pixii has a 26MP APS-C sensor, a 64-bit processor, 3 finder frame lines and a nicely made rangefinder.

Fujifilm X100V: This ingenious APS-C-format camera incorporates a 26.1MP X-Trans CMOS 4 BSI sensor that provides an ISO 160-12800 sensitivity range and an expanded phase-detection autofocus system that utilizes 425 selectable points It can record 4K video at 30fps, shoot full HD videos at up to 120fps, and sports a non-interchangeable Fujinon 23mm f/2 lens with two aspherical elements. Its signature feature: an Advanced Hybrid Viewfinder that lets you switch between optical and electronic viewfinders at the press of a lever on the front of the camera. The 0.52x-magnification optical viewfinder provides a clear, lifelike view of the scene for easier composition and subject tracking. Its enhanced design incorporates an Electronic Rangefinder function, which mimics the functionality of a mechanical rangefinder, and simultaneously overlays information from the electronic viewfinder on top of the optical viewfinder for comparative manual focus control. The electronic viewfinder provides detailed 3.69m-dot resolution along with a fast refresh rate to reduce lag for smoother panning and tracking movements; the electronic rangefinder offers a 4-tier split-image function or an electronic microprism to assist manual focusing. Obviously aimed at sophisticated digital shooters that hanker for a few retro features to provide a traditional shooting experience, the X100V is available in silver or black at $1,399.00.

Other rangefinder cameras: a brief and incomplete survey

There are scads of fascinating analog rangefinder 35s we can’t possibly detail in this article. Here are a few worth mentioning in passing:

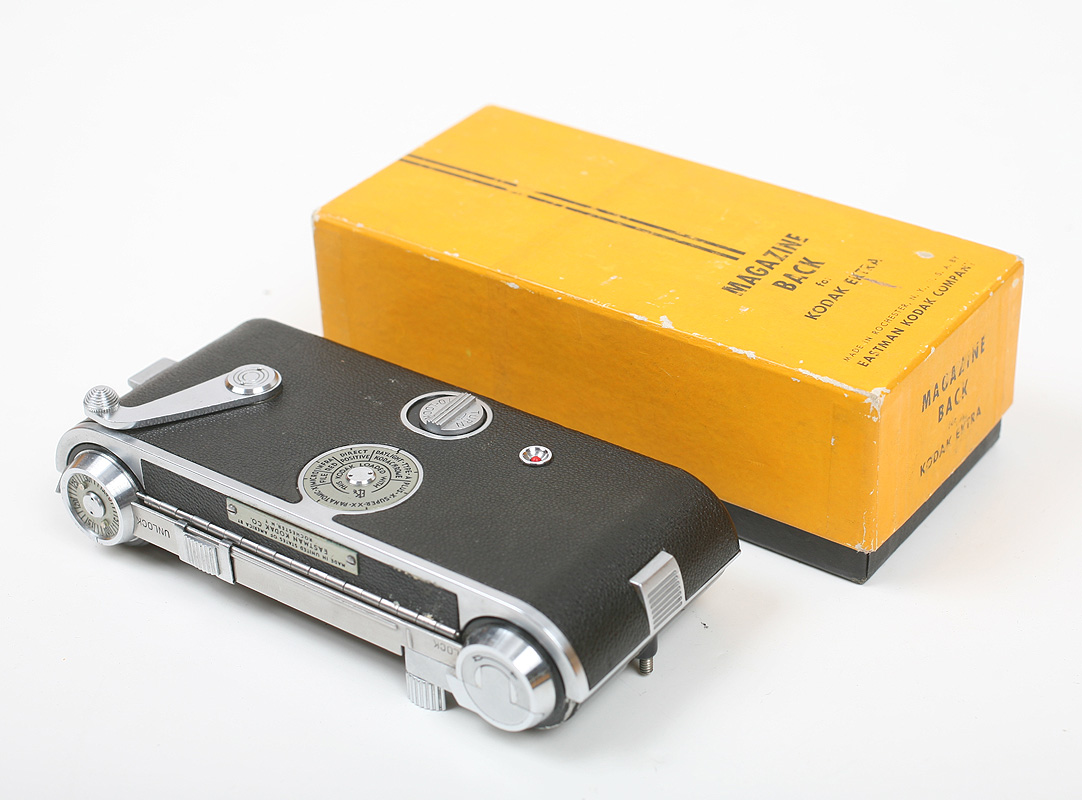

The Kodak Ektra was designed to go up against the Leica and the Contax, but its complexity, high price and wonky shutter doomed it.

The Kodak Ektra (1941-1948): Kodak’s first and last attempt to build a world class interchangeable lens rangefinder system to challenge Leica and Zeiss was a magnificent failure due to its extreme complexity, stratospheric price, and ingenious but notoriously unreliable shutter. It had a separate manually set zoom finder, interchangeable backs, and a superb line of lenses, but its crowning glory was its military grade split-image prism rangefinder which has a base length of an astounding 4-1/8 inches and a magnification of 1.6x to accommodate a planned but never produced 254mm lens. This of course made it impossible to use a combined range/viewfinder, so there are separate eyepieces for viewing and focusing. It’s a very good rangefinder and very accurate but not the last word in brightness, so looking through it is an underwhelming experience. Agfa also offered two fixed lens, leaf shutter 35s with nice split-image rangefinders in the ‘50s, the Agfa Karat and Karomat, either of which was available with the excellent 50mm f/2 Solagon lens.

Two German rangefinder 35s with Compur leaf shutters and interchangeable lenses were the Voigtlander Prominent (models I and II) and the Kodak Retina IIIC, the latter using interchangeable front components rather than fully interchangeable lenses. Both had very nice superimposed- image rangefinders, and the Retina’s multi-frame range/viewfinder has a very well-defined rangefinder patch and can be used as a split-image rangefinder in the same manner as a Leica M.

The Konica Hexar RF (1999-2003) accepts M-mount lenses and has an excellent range/viewfinder with 6 parallax-compensating frame lines that appear in pairs, and its crisply defined rangefinder patch can be used for both superimposed-image and split-image focusing according to the manual. Used price range: $800-$1,200, body only.

Voigtlander Bessa R3A, shown with M-mount 40mm f/1.4 Nokton offered AE, multiple frame lines and a life-size 1.0x viewfinder,

The Voigtlander line of M-mount rangefinder cameras made by Cosina was produced in a variety of specifications, but all are attractive, well- made, competent cameras that are noticeably more compact, lightweight, and affordable than comparable Leicas. They have user-selectable projected, parallax compensating frame line finders for multiple focal lengths, a rangefinder base length of 37mm (for the 1.0x R3A), a viewfinder magnification of 0.7x, for an effective rangefinder base length of 25.6, satisfactory for most purposes. All have well defined rangefinder patches, and the manuals specifically describe how they can be used for superimposed image and split image focusing.

Rangefinder camera plusses and minuses:

Advantages:

1.Rangefinder cameras can focus wide-angle lenses more precisely than SLRs because focusing is not dependent on observing the sharpness of the visual image formed by the lens on the focusing screen. Focusing screens with split-image and microprism aids help but don’t fully eliminate for this discrepancy.

2.The brightness of view through range/viewfinder system is not dependent on the aperture of the lens used. It is equally bright no matter which lens is fitted, an advantage in low light shooting.

3.With a rangefinder camera you can see the area beyond the actual framing area, making it possible to anticipate action before it enters the frame and release the shutter at the right instant.

4.Rangefinder cameras do not need a mirror box or flipping mirror, which is why they’re generally quieter and less prone to camera shake than SLRs and have more compact form factors. Indeed, these assets explain why mirrorless cameras have now largely supplanted SLRs and DSLRs even among pros.

5Focusing a rangefinder camera manually is very decisive—you superimpose or align the two (or more) images and you’re done. without any back-and-forth required to achieve precise focus.

Disadvantages:

1.No rangefinder camera lets you preview the captured image with 100% accuracy with any lens mounted on the camera like an SLR or mirrorless camera. Even the Leica M, which does much better than most, isn’t perfect in this respect.

2.The maximum practical focal length useable with a full-frame rangefinder camera is about 135mm, and many believe that 90mm is a more realistic cutoff point. Long telephotos and zoom lenses are really the province of mirrorless cameras and SLRs.

3.The focusing accuracy of rangefinder cameras is limited by the inevitable focal length variance among lenses that come off the production line, which must be (imperfectly) compensated by matching the rangefinder coupling cam profile to the individual lens so nearly perfect focus can be achieved when aligning the stationary and moving rangefinder images. The traditional aim point of “50mm” Leica lenses is 51.6mm and Leitz separated lenses into depending on their actual focal lengths and made an extensive range of cams to match the actual focal length of any lens that was in spec according to their tests.

4.The actual magnification factor of most range/viewfinder systems is less than life-size (1:1), though there are exceptions such ss the Voigtlander Bessa R3A.

How to focus and shoot with a rangefinder camera:

First, make sure the eyepiece is adjusted to your vision by observing a detailed, contrasty subject at infinity and turning the eyepiece focusing control until the viewing image and the rangefinder patch are perfectly sharp. Now place your viewing (master) eye directly behind the viewfinder eyepiece (not obliquely!), place the central rangefinder patch over your focusing target (subject area) so it appears as two distinct and separate images when the subject is out of focus. If the subject is technical or architectural with distinct vertical lines (like a telephone pole or a church tower), mentally form a split image rangefinder by using the rangefinder patch as the central band, and the areas directly above and below the rangefinder patch as the upper and lower bands, and turn the focusing control of the lens until all 3 bands are in perfect alignment. This is, by a factor of about 5, the most accurate focusing method.

Page from the Zeiss-ikon ZM manual showing and explaining the superimposed image (top) and split-image rangefinder focusing methods.

If the subject is more amorphous or lacks straight lines (e.g., a human face or a bowl of fruit) the superimposed image (coincident) method works best—just bring the moving and stationary images together by placing one directly over the other to form a single image with absolutely zero lateral displacement or double edges visible. With a rangefinder camera you can also set the focusing ring of the lens at a fixed distance, say 10 feet, track a moving subject with the rangefinder patch, and fire when the 2 images coincide—an old- fashioned version of the “trap focus” system option available with many of today’s DSLRs and mirrorless cameras. No rangefinder camera is as convenient as an autofocus camera or the one built into your smartphone, but you picked a rangefinder camera because it provides a different shooting experience, one in which the photographer is more involved in shaping the picture taking process. Whether this results in more compelling images is entirely up to you—but that’s the point!

How to get the most out of everybody’s favorite vintage classics.

By Jason Schneider

I bought my first Leica in 1960—a “window display” Leica IIIg with collapsible 50mm f/2.8 Elmar lens at a whopping 10% off the list price—and I haven’t been the same since. Over the ensuing years I’ve acquired and shot with innumerable rangefinder 35s including Barnack and M Leicas, a splendid variety Canons, a few Nikons, and far too many Contaxes, both prewar and postwar. Despite my undying affection for the breed, rangefinder 35s have their peccadillos and it helps to have a clear grasp of their assets, liabilities, and operating characteristics if you expect to get the most out of them. Let’s start by taking a quick trip down memory lane.

The Leica II (Model D) of 1932, a masterpiece of minimalist ingenuity, sired a generation of screw-mount "Barnack" Leicas that ended in 1960.

The first successful rangefinder 35 was the Leica II, Model D, of 1932 (its archrival, the Contax I released in the same year, had a notoriously unreliable shutter). Essentially the Leica II (Model D) was nothing more than a Leica I (Model C) with interchangeable screw mount lenses on the front and a coupled short base, high magnification (1.5x) rangefinder with a separate optical viewfinder shoehorned into a small housing on the top. The genius of the design was coupling the screw mount lenses to the rangefinder by means of a brass cam on the back of each lens that contacts a roller at the end of a spring-loaded arm inboard of the lens mount. Turning the focusing lever (or ring) of a mounted lens controls the position of the moving coincident rangefinder image so that proper focus is achieved when the moving and fixed (circular) images of the rangefinder coincide (are no longer laterally displaced).

Building all this into a camera virtually the same size as the original “miniature” Leica A was a stunning achievement, and it endured (with various tweaks and modifications) until 1954, when the landmark Leica M3 was announced, and lingered until 1960 when the last screw mount Leica IIIg rolled off the production line. All screw-mount Leicas have reasonably well-defined, very clear circular rangefinder patches, but they’re optimized for superimposed image (coincident) focusing and don’t lend themselves to using the inherently more accurate split-image focusing method. All have less convenient separate viewfinders, and all but the Leica IIIg have small fixed 50mm viewfinders that necessitate using a separate shoe mount accessory viewfinder when shooting with lenses other than 50mm.

Enter the Leica M3: Pioneering the greatest range/viewfinder of all.

The Leica M3 1954 was widely hailed as the finest interchangeable-lens 35mm rangefinder camera ever made, the most advanced practical rangefinder 35 of its day, and the first new-from-the-ground-up Leica in nearly 40 years. The most significant advances in the M3 are a magnificent long base (68.5mm) nearly life-size (0.91X) combined range/viewfinder with true projected, parallax-compensating, auto-indexing frame lines for 50mm, 90mm, and 135mm lenses, the M-type bayonet mount, a two-stroke film-advance lever (later modified to provide single-stroke operation), and a hinged back section to facilitate cleaning, shutter checking, and film alignment. A translucent light-collecting window in between the rangefinder and viewfinder windows provides illumination for the bright, crisp white finder frame lines, and a frame line-selector lever below the front viewfinder window lets you previsualize the effect of mounting other lenses. But merely enumerating its outstanding features hardly does justice to this exquisitely refined machine. The integration of its various components is brilliant. It’s rubberized, 1-1/1000 sec plus B, horizontal travel cloth focal plane shutter is whisper quiet. Its contours mold seamlessly to your hands, and its shutter release, wind lever, and focusing mount operate with an uncanny silky precision. Within a few years, leading Japanese manufacturers, notably Nikon and Canon, produced splendid rivals to the Leica M3 with multi-frame range/viewfinders (see section below) and much more, but none ever equaled, much less surpassed the Leica in terms of overall excellence of design, particularly its superb range/viewfinder, which is yet to be natched by any full frame analog or digital rangefinder camera terms of focusing ease and precision. Perhaps the greatest tribute to the Leica M3 (aside from the legacy of memorable images it has captured) is the fact that it still endures. The current Leica MP and M6 are really nothing more than upgraded M3’s with additional finder frames and built in TTL metering, and the late, lamented M7 is basically an upgraded M3 with built-in autoexposure. And of course, all former and current digital Leica M’s culminating in the present top-of-the-line M11 are built upon the concept and features the M3 set forth nearly 70 years ago.

The Leica M3 of 1954 was a game changer that transformed the interchangeable lens rangefinder 35. I still lives in every analog and digital M.

The Leica M3, and its illustrious stable mates the M2 and M4 are all great (and now rather pricey) user collectibles selling in the $1,500 range in chrome (body only) in clean working condition (prices vary widely so check before pulling the trigger). The single-stroke M3 of the mid-60’s, with more rugged, durable wind and shutter mechanisms, a larger exit pupil for enhanced finder brightness, and serial number above 1,100,000, is especially prized (and more expensive), and early two-stroke models in average condition are more affordable.

Competing with the Leica M? No contest!

To say that the Leica M3 created a sensation and shocked the engineers at Canon, Nikon, and Zeiss when it officially debuted at Photokina 1954 is an understatement. Indeed, the Leica’s competitors were literally blown into the weeds—and they knew it. The top Canon at the time was the bottom loading screw mount Canon IVSB (marketed in the U.S. as the IVS2), which had a tiny range/viewfinder with three magnification settings but no viewfinder frame lines. Nikon offered the Nikon S, which weighs a ton, has a well-executed but dinky range/viewfinder, and a non-standard 24x34mm format. In response to the M3 Nikon brought forth the Nikon S2 in 1955, the first Japanese camera with a film wind lever, rewind crank, and a life-size 1:1 range/viewfinder with a fixed reflected 50 mm frame line—a lovely camera but no match for the mighty M3. Zeiss-Ikon brought forth the Contax IIa/IIIa in 1950, basically a pared down, lighter, slightly smaller, much more reliable versions of the prewar Contax II and III. Like their forbears they had removable backs, a superb line of Contax bayonet mount lenses, and a high quality but smallish range/viewfinder with no frame lines. Sadly (and perhaps wisely) this was to be the final iteration of the classic rangefinder Contax, as Zeiss declined to enter the “rangefinder finder frame line wars” that took place in the mid to late ‘50s among Leica, Nikon, and Canon. By 1959 when the game-changing Nikon F SLR was introduced, Leica had tacitly emerged victorious, although Nikon technically produced a few multi-frame successors to the 1957 Nikon SP in the ‘60s. and Canon soldiered on with the 5-frame-line 7sZ until late 1968.

Nikon S2 of 1955 was Nikon's response to the all-conquering Leica M3. It's a beautiful camera with great features, but not in the same league.

Nikon SP of 1957-1960 want head to head with the Leica M's. It had more finder frame lines, but it never really challenged the M3,M2, and M4.

The glorious Canon 7sZ of 1968, last of the classic rangefinder Canons, has a built in CdS meter and an excellent multi-frame range/viewfinder.

What makes the Leica M range/viewfinder so special?

As the accompanying range/viewfinder diagram taken from Kisselbach’s excellent “The Leica Book” from the 1950s shows, the path of the light passing through the front rangefinder window passes through a solid double deflecting glass prism and is projected through a “telescopic element” coupled to the lens focusing system and into the viewfinder. The field frame illuminated by the central translucent window lies in precisely the same plane. The field frame and rangefinder images (rays) are simultaneously reflected by a beam-splitter into the viewfinder eyepiece where they are joined by the ray coming from the viewfinder, thereby producing a double image of the sighted object. By moving the focusing ring or tab of the lens, these images move closer together or further apart, and when the lens is focused correctly, they merge into a single image.

'50s brochure on the Leica M3 extols the virtues if its range/viewfinder with an excellent schematic showing how it works. Those were the days!

The focusing accuracy of this system is extremely high because the rangefinder patch is so clearly delineated that it’s possible to focus using the traditional coincident (superimposed image) method and also to use the areas above and below the patch to visually form, in effect, a split image rangefinder, that lets you focus by “reconstructing” a broken vertical or oblique line running through the viewfinder images and the rangefinder patch. In addition, the entire projected frame line moves laterally and vertically as the lens is focused to various distances, automatically correcting the parallax error that would otherwise exist between the viewfinder and the camera lens. Other multi-frame range/viewfinder systems (notably those in late model Nikon and Canon rangefinder cameras) provide automatic parallax compensation for a range of focal lengths, but none provide auto indexing, which automatically displays the appropriate frames when you mount a lens, and none is optimized for focusing using the split-image focusing method, claimed by experts to be about 5 times more precise than using the superimposed image (coincident) method.

According to the leading Leica repair experts we spoke with, the Leica M range/viewfinder system affords the following unique advantages:

1.The magnification of the rangefinder patch matches the viewing area very precisely.

2.The rangefinder patch is perfectly symmetrical within the frame line in use and remains centered when lenses of different focal lengths are used, and when the lens is focused.

3.Both the central rangefinder patch and the projected frame lines are crisp and sharp and appear at the same plane as you look through the viewfinder. Two thin pieces of metal provide the frame line parallax compensation for all focal lengths.

Other cool and competent range/viewfinder systems

While there’s no standard production range/viewfinder system that surpasses the one built into Leica M cameras, there is a selection of fascinating alternatives, past and present. Not surprisingly, both the Leica/Leitz Minolta CL and the Minolta CLE (both the results of a longstanding collaboration between Leitz and Minolta) are M-mount rangefinder cameras that use a simplified version of the Leica M range/viewfinder system, and the user manuals for both cameras specifically describe the split-image focusing method and recommend using it to achieve greater focusing accuracy. However, neither one provides the same degree of focusing accuracy as a Leica M.

The Minolta CLE was best camera to emerge from the Leitz/Minolta partnership of the '70s, but Leitz never made lenses specifically for it.

The rangefinder base of the CL is 31.5mm and the viewfinder magnification is 0.60x, resulting in a small effective rangefinder base (EBL) of 18.9 mm. This is too short for accurate focusing with lenses longer than 90mm and fast lenses used at full aperture. The Minolta CLE does better, with an actual rangefinder base length of 49.6mm, a viewfinder magnification of 0.58x and an effective base length of 28.9mm. Both cameras display projected parallax compensating frame lines for 40mm, 50mm, and 90mm lenses. An analog Leica or Leitz Minolta CL body in good shape runs about $350 to $700; a clean functional Minolta CLE will set you back $500-$750, body only.

The Zeiss Ikon ZM of 2005 to 2012 (sometimes simply referred to as the Zeiss Ikon) is a handsome and fascinating M-mount rangefinder camera made by Cosina, designed with input from Zeiss, and compatible with M and LTM-mount lenses by Zeiss (or Leica et al). Its excellent range/viewfinder has a magnification of 0.74x, an actual rangefinder base length of 75mm, and an effective base length of 55.5mm, making it useable with a wider variety of lenses than the CL and CLE. It provides projected, auto indexing, parallax compensating frame lines for 28/85mm (simultaneously), 35mm, and 50mm, offers aperture priority autoexposure like the Minolta CLE, and the manual specifically cites and illustrates its split-image focusing capability. The ZM has one flaw which may or may not be fatal depending on your priorities—its rangefinder mechanism is rather delicate and easy to knock out of whack with rough handling or an incidental impact. It may be OK for general use but it's probably not the best choice for banging around on the trail. ZM’s are also not for the faint of wallet; a clean functional example in black or chrome runs $1,200 to $2,000 body only depending on the specifics.

Zeiss Ikon ZM, made by Cosina with input by Zeiss, is one if the nicest non-Leica M-mount 35's but its rangefinder mechanism is delicate .

Pixii: Leave it to the French to come up with an offbeat but workable take on the M-mount digital rangefinder camera. Originally released in 2018, the latest 26MP APS-C sensor version of 2023 has an “interactive viewfinder” and a new 64-bit quad-core ARM Cortex-A55 processor with a dual-core OpenCL 2.O GPU with 768 threads and speeds up to 7G pixels/sec along with dedicated NPU and VPU cores. As a result, the company claims its latest model is the first color camera capable of capturing true monochrome DNGs and highlights the 64-bit processor’s ability to resolve finer details and create smoother transitions. Pixii claims the new camera can process images 10x faster than previous versions, provides three times faster transfer speeds and extends battery life by 25%. The Pixii has no EVF or LCD (other than a small back-mounted Status Indicator LCD) and is designed to display captured images on a paired device such as a smartphone. However, its optical viewfinder includes parallax compensating frame lines for 28mm, 35mm, and 50mm lenses, exposure indicators at the bottom. and a nice crisply defined rangefinder patch in the center, which is used for manually focusing attached lenses in the traditional manner. While not specifically mentioned in the manual both the superimposed image and split image focusing methods are clearly useable with this camera. An advanced an ingenuous niche product, the latest Pixii sells for $2,800.

Latest 2023 version the French made Pixii has a 26MP APS-C sensor, a 64-bit processor, 3 finder frame lines and a nicely made rangefinder.

Fujifilm X100V: This ingenious APS-C-format camera incorporates a 26.1MP X-Trans CMOS 4 BSI sensor that provides an ISO 160-12800 sensitivity range and an expanded phase-detection autofocus system that utilizes 425 selectable points It can record 4K video at 30fps, shoot full HD videos at up to 120fps, and sports a non-interchangeable Fujinon 23mm f/2 lens with two aspherical elements. Its signature feature: an Advanced Hybrid Viewfinder that lets you switch between optical and electronic viewfinders at the press of a lever on the front of the camera. The 0.52x-magnification optical viewfinder provides a clear, lifelike view of the scene for easier composition and subject tracking. Its enhanced design incorporates an Electronic Rangefinder function, which mimics the functionality of a mechanical rangefinder, and simultaneously overlays information from the electronic viewfinder on top of the optical viewfinder for comparative manual focus control. The electronic viewfinder provides detailed 3.69m-dot resolution along with a fast refresh rate to reduce lag for smoother panning and tracking movements; the electronic rangefinder offers a 4-tier split-image function or an electronic microprism to assist manual focusing. Obviously aimed at sophisticated digital shooters that hanker for a few retro features to provide a traditional shooting experience, the X100V is available in silver or black at $1,399.00.

Other rangefinder cameras: a brief and incomplete survey

There are scads of fascinating analog rangefinder 35s we can’t possibly detail in this article. Here are a few worth mentioning in passing:

The Kodak Ektra was designed to go up against the Leica and the Contax, but its complexity, high price and wonky shutter doomed it.

The Kodak Ektra (1941-1948): Kodak’s first and last attempt to build a world class interchangeable lens rangefinder system to challenge Leica and Zeiss was a magnificent failure due to its extreme complexity, stratospheric price, and ingenious but notoriously unreliable shutter. It had a separate manually set zoom finder, interchangeable backs, and a superb line of lenses, but its crowning glory was its military grade split-image prism rangefinder which has a base length of an astounding 4-1/8 inches and a magnification of 1.6x to accommodate a planned but never produced 254mm lens. This of course made it impossible to use a combined range/viewfinder, so there are separate eyepieces for viewing and focusing. It’s a very good rangefinder and very accurate but not the last word in brightness, so looking through it is an underwhelming experience. Agfa also offered two fixed lens, leaf shutter 35s with nice split-image rangefinders in the ‘50s, the Agfa Karat and Karomat, either of which was available with the excellent 50mm f/2 Solagon lens.

Two German rangefinder 35s with Compur leaf shutters and interchangeable lenses were the Voigtlander Prominent (models I and II) and the Kodak Retina IIIC, the latter using interchangeable front components rather than fully interchangeable lenses. Both had very nice superimposed- image rangefinders, and the Retina’s multi-frame range/viewfinder has a very well-defined rangefinder patch and can be used as a split-image rangefinder in the same manner as a Leica M.

The Konica Hexar RF (1999-2003) accepts M-mount lenses and has an excellent range/viewfinder with 6 parallax-compensating frame lines that appear in pairs, and its crisply defined rangefinder patch can be used for both superimposed-image and split-image focusing according to the manual. Used price range: $800-$1,200, body only.

Voigtlander Bessa R3A, shown with M-mount 40mm f/1.4 Nokton offered AE, multiple frame lines and a life-size 1.0x viewfinder,

The Voigtlander line of M-mount rangefinder cameras made by Cosina was produced in a variety of specifications, but all are attractive, well- made, competent cameras that are noticeably more compact, lightweight, and affordable than comparable Leicas. They have user-selectable projected, parallax compensating frame line finders for multiple focal lengths, a rangefinder base length of 37mm (for the 1.0x R3A), a viewfinder magnification of 0.7x, for an effective rangefinder base length of 25.6, satisfactory for most purposes. All have well defined rangefinder patches, and the manuals specifically describe how they can be used for superimposed image and split image focusing.

Rangefinder camera plusses and minuses:

Advantages:

1.Rangefinder cameras can focus wide-angle lenses more precisely than SLRs because focusing is not dependent on observing the sharpness of the visual image formed by the lens on the focusing screen. Focusing screens with split-image and microprism aids help but don’t fully eliminate for this discrepancy.

2.The brightness of view through range/viewfinder system is not dependent on the aperture of the lens used. It is equally bright no matter which lens is fitted, an advantage in low light shooting.

3.With a rangefinder camera you can see the area beyond the actual framing area, making it possible to anticipate action before it enters the frame and release the shutter at the right instant.

4.Rangefinder cameras do not need a mirror box or flipping mirror, which is why they’re generally quieter and less prone to camera shake than SLRs and have more compact form factors. Indeed, these assets explain why mirrorless cameras have now largely supplanted SLRs and DSLRs even among pros.

5Focusing a rangefinder camera manually is very decisive—you superimpose or align the two (or more) images and you’re done. without any back-and-forth required to achieve precise focus.

Disadvantages:

1.No rangefinder camera lets you preview the captured image with 100% accuracy with any lens mounted on the camera like an SLR or mirrorless camera. Even the Leica M, which does much better than most, isn’t perfect in this respect.

2.The maximum practical focal length useable with a full-frame rangefinder camera is about 135mm, and many believe that 90mm is a more realistic cutoff point. Long telephotos and zoom lenses are really the province of mirrorless cameras and SLRs.

3.The focusing accuracy of rangefinder cameras is limited by the inevitable focal length variance among lenses that come off the production line, which must be (imperfectly) compensated by matching the rangefinder coupling cam profile to the individual lens so nearly perfect focus can be achieved when aligning the stationary and moving rangefinder images. The traditional aim point of “50mm” Leica lenses is 51.6mm and Leitz separated lenses into depending on their actual focal lengths and made an extensive range of cams to match the actual focal length of any lens that was in spec according to their tests.

4.The actual magnification factor of most range/viewfinder systems is less than life-size (1:1), though there are exceptions such ss the Voigtlander Bessa R3A.

How to focus and shoot with a rangefinder camera:

First, make sure the eyepiece is adjusted to your vision by observing a detailed, contrasty subject at infinity and turning the eyepiece focusing control until the viewing image and the rangefinder patch are perfectly sharp. Now place your viewing (master) eye directly behind the viewfinder eyepiece (not obliquely!), place the central rangefinder patch over your focusing target (subject area) so it appears as two distinct and separate images when the subject is out of focus. If the subject is technical or architectural with distinct vertical lines (like a telephone pole or a church tower), mentally form a split image rangefinder by using the rangefinder patch as the central band, and the areas directly above and below the rangefinder patch as the upper and lower bands, and turn the focusing control of the lens until all 3 bands are in perfect alignment. This is, by a factor of about 5, the most accurate focusing method.

Page from the Zeiss-ikon ZM manual showing and explaining the superimposed image (top) and split-image rangefinder focusing methods.

If the subject is more amorphous or lacks straight lines (e.g., a human face or a bowl of fruit) the superimposed image (coincident) method works best—just bring the moving and stationary images together by placing one directly over the other to form a single image with absolutely zero lateral displacement or double edges visible. With a rangefinder camera you can also set the focusing ring of the lens at a fixed distance, say 10 feet, track a moving subject with the rangefinder patch, and fire when the 2 images coincide—an old- fashioned version of the “trap focus” system option available with many of today’s DSLRs and mirrorless cameras. No rangefinder camera is as convenient as an autofocus camera or the one built into your smartphone, but you picked a rangefinder camera because it provides a different shooting experience, one in which the photographer is more involved in shaping the picture taking process. Whether this results in more compelling images is entirely up to you—but that’s the point!

Last edited: