The Camera: It’s Much More Than Just A Tool

The photographer-camera interface has a profound effect on the images seen by the viewer

By Jason Schneider

The magic of photography is that it can transform the physical and emotional act of selective observation into a visual artifact that transcends the moment of its creation and places it in the context of eternity. Miraculously, a photograph can convey the consciousness of the photographer across time and space, producing a corresponding visceral and emotional response in anyone who takes the time to fully engage with the image. And perhaps even more astounding, the entire process can be accomplished by controlling just two irreducible variables—space (what’s in the frame) and time (when do you press the shutter release).

Obviously, there are often many other factors that go into creating a photograph, and each one can be a decision point that materially affects the end result—the camera chosen, the sensor or film used, the ISO setting, the viewing angle of the lens, the shooting aperture, the shutter speed, the lighting, etc., etc. Nevertheless, what is captured on the light sensitive medium, and at what precise instant that capture occurs are the most basic and crucial elements under the photographer’s control. Indeed, they’re implicit even when an automated camera is installed at a fixed location and the frames or video clips deemed most relevant are selected afterwards.

Yes, for all these and many other reasons there’s great truth in the old saw that, “It’s not the camera, but the photographer that makes the picture.” But in a deeper sense, a photograph is a visual representation of the dialog between the photographer and the subject as mediated through the physical act of taking the picture. That’s why I totally agree with the nameless portrait photographer who first said, “The subject is everything—I’m merely the photographer.” However, the camera itself, and more specifically the camera-photographer interface, can also have a profound influence on the look and feel, and even the emotional aspect of the resulting images.

In other words, the camera is not, as many have claimed, the mere analog of the painter’s brushes or the writer’s pen or computer, which are incidental to creating, say, a grand oil painting or a The Great American Novel. The camera and its accoutrements form an integral part of the creative process of photography because photography, unlike the classic visual arts of painting and sculpture, is a technologically based artform. That’s why the type of camera a photographer uses shapes the way he or she approaches the act of taking the picture, resulting in distinct visual differences that are deeply embedded in the character and even the informational content of the ensuing photographs.

These differences are especially evident in portraits because the photographer’s working relationship with the subject is intimate, intense, and interactive, and the photographer’s goal is to create an image that reveals something about the identity and state of being of the subject. To highlight these differences I’ve chosen two pairs of portraits, each of the same subject, shot with two of my favorite cameras—a Sigma fp high-performance 24.6MP full-frame mirrorless digital camera, and my ancient analog Mamiya C220 6x6 cm twin lens reflex of 1968, which was loaded with Ilford HP-5 Plus black & white film, shot at ISO 400, developed normally, and scanned at hi-res. In both cases, the camera was fitted with its excellent normal prime lens—a Sigma 45mm f/2.8 DG DN on the Sigma; the 80mm f/2.8 Mamiya-Sekor (old style) lens set on the Mamiya TLR.

Reactions to photographs of any kind are intensely personal, and the most important and valid impressions and feelings regarding these portraits, and the entire premise of this article for that matter, are yours, not mine. However, I’ve included my own thoughts on these images in extended captions in the hope they may provide a clearer understanding of where I’m coming from. I welcome your comments and suggestions with one caveat. I know perfectly well that the camera-photographer interface is not the sole determinant of the character and content of an image, and that the correlations I’ve noted here refer to general tendencies not one-to-one correspondences.

For example, I’ve personally captured a classic New York City “street scene” that looks like it could’ve been shot with a Leica, but I actually used a tripod-mounted 8 x 10 view camera –it just happened to be set to the right distance and aperture when I swung the camera around and grabbed it. I’ve also seen many crisp, beautifully composed landscapes (including one by Ansel Adams) that were taken not with large-format view camera, but with a humble box camera. Nevertheless, I do believe that the choice of camera does affects the way the photographer makes the shot, and I sure hope you can appreciate the fascinating differences I’ve showcased here.

Thoughts on the images

Maddie, Age 11, Sigma fp with 45mm lens: Beautiful, natural, discreetly smiling expression of a “tween” coming into womanhood. It exudes joy, confidence, directness, and openness, capturing key aspects or her charming and engaging personality.

Maddie, Age 11, Mamiya C220 with 80mm lens: This more contemplative pose is far less assertive, revealing the subject’s vulnerability. It embodies the tentative, fragile quality of a pre-teen in the process of discovering and shaping her own identity, though one can also sense an underlying strength, determination, and openness to the future that presages a successful transition to womanhood. The color image is a more flattering and appealing portrait, but I think this image says more about the subject and the distinctive rendition possible with a medium format twin lens reflex film camera.

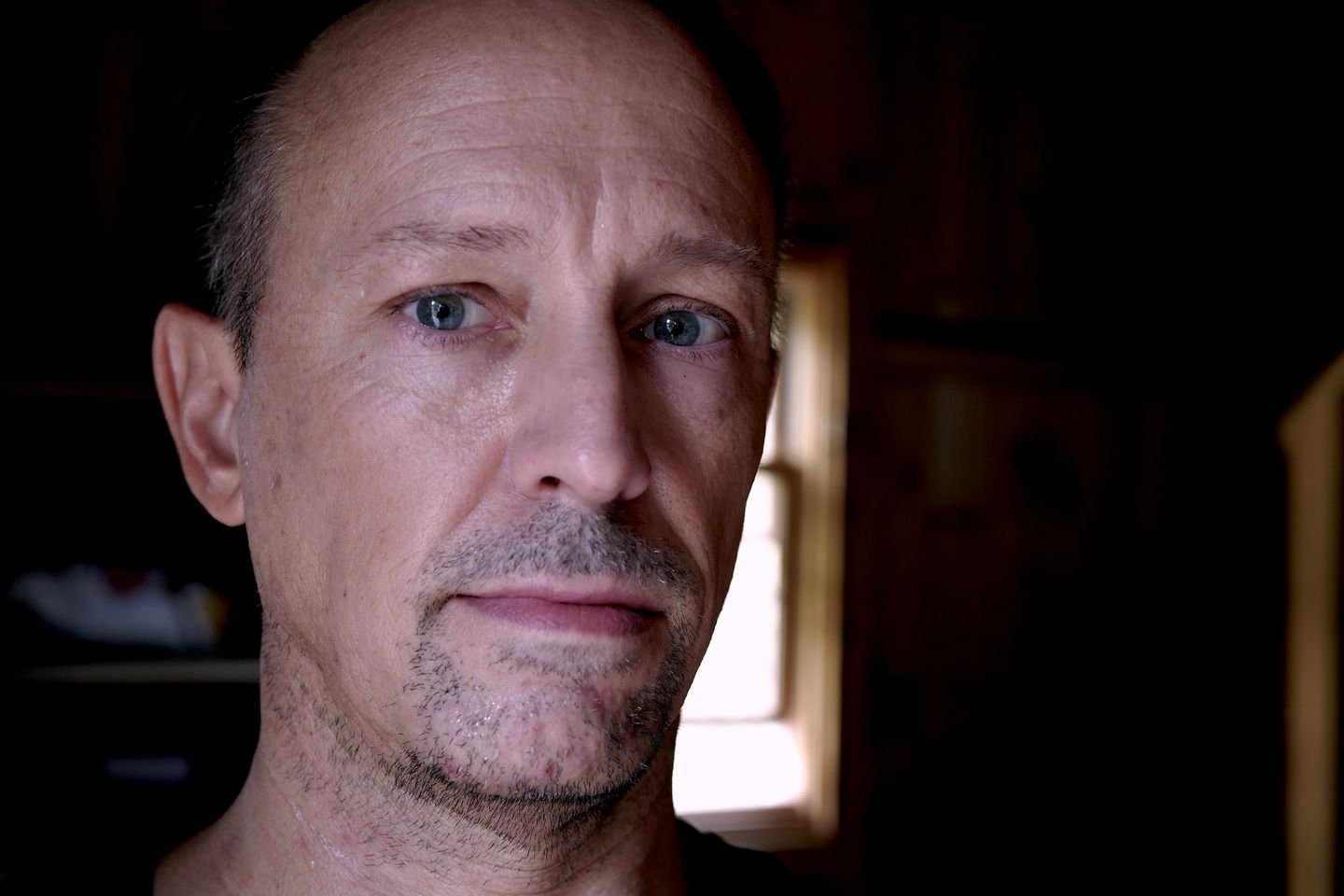

Sean, Sigma fp with 45mm lens: This is a strong and compelling portrait that conveys the sense of a person who knows who he is and stands by his convictions. However, the relatively flat, partially backlit lighting does not delineate the facial structure as well as the corresponding black & white image does. While the impression of fortitude, presence, and engagement is still evident it’s not expressed as strongly as it is in the black & white portrait.

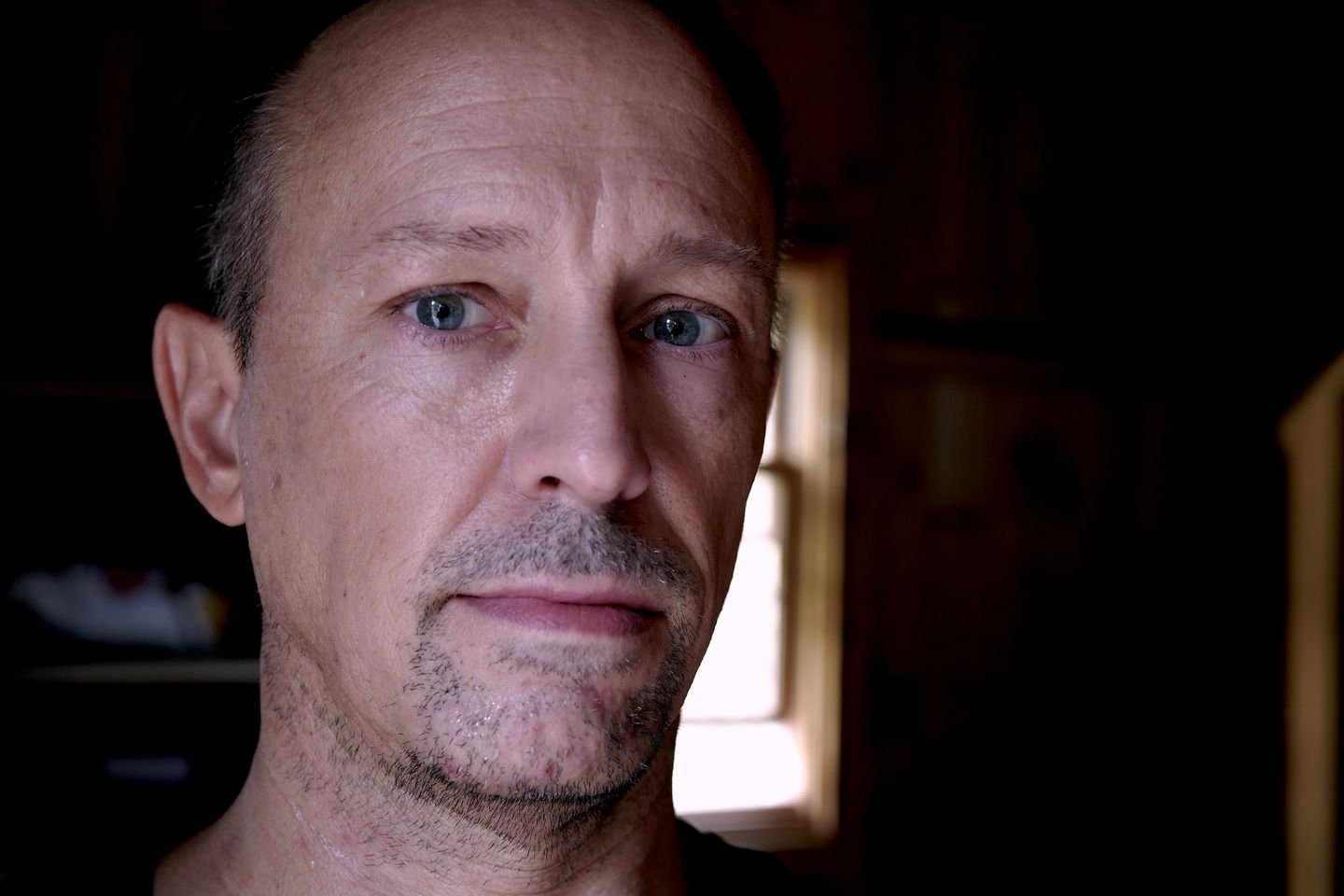

Sean, Mamiya C220 with 80mm lens: This is a very powerful and successful portrait and the subject’s face is beautifully delineated by strongly directional widow light. The direct eye contact and calm, pleasant, determined expression convey strength of character, but also a thoughtful and sympathetic quality that is very attractive and engaging. He looks like a guy you can trust and depend on and the image also conveys a sense of self-awareness, focused intelligence, and discernment. It’s a testament to what you can do with an ancient analog TLR with close focusing ability.

The photographer-camera interface has a profound effect on the images seen by the viewer

By Jason Schneider

The magic of photography is that it can transform the physical and emotional act of selective observation into a visual artifact that transcends the moment of its creation and places it in the context of eternity. Miraculously, a photograph can convey the consciousness of the photographer across time and space, producing a corresponding visceral and emotional response in anyone who takes the time to fully engage with the image. And perhaps even more astounding, the entire process can be accomplished by controlling just two irreducible variables—space (what’s in the frame) and time (when do you press the shutter release).

Obviously, there are often many other factors that go into creating a photograph, and each one can be a decision point that materially affects the end result—the camera chosen, the sensor or film used, the ISO setting, the viewing angle of the lens, the shooting aperture, the shutter speed, the lighting, etc., etc. Nevertheless, what is captured on the light sensitive medium, and at what precise instant that capture occurs are the most basic and crucial elements under the photographer’s control. Indeed, they’re implicit even when an automated camera is installed at a fixed location and the frames or video clips deemed most relevant are selected afterwards.

Yes, for all these and many other reasons there’s great truth in the old saw that, “It’s not the camera, but the photographer that makes the picture.” But in a deeper sense, a photograph is a visual representation of the dialog between the photographer and the subject as mediated through the physical act of taking the picture. That’s why I totally agree with the nameless portrait photographer who first said, “The subject is everything—I’m merely the photographer.” However, the camera itself, and more specifically the camera-photographer interface, can also have a profound influence on the look and feel, and even the emotional aspect of the resulting images.

In other words, the camera is not, as many have claimed, the mere analog of the painter’s brushes or the writer’s pen or computer, which are incidental to creating, say, a grand oil painting or a The Great American Novel. The camera and its accoutrements form an integral part of the creative process of photography because photography, unlike the classic visual arts of painting and sculpture, is a technologically based artform. That’s why the type of camera a photographer uses shapes the way he or she approaches the act of taking the picture, resulting in distinct visual differences that are deeply embedded in the character and even the informational content of the ensuing photographs.

These differences are especially evident in portraits because the photographer’s working relationship with the subject is intimate, intense, and interactive, and the photographer’s goal is to create an image that reveals something about the identity and state of being of the subject. To highlight these differences I’ve chosen two pairs of portraits, each of the same subject, shot with two of my favorite cameras—a Sigma fp high-performance 24.6MP full-frame mirrorless digital camera, and my ancient analog Mamiya C220 6x6 cm twin lens reflex of 1968, which was loaded with Ilford HP-5 Plus black & white film, shot at ISO 400, developed normally, and scanned at hi-res. In both cases, the camera was fitted with its excellent normal prime lens—a Sigma 45mm f/2.8 DG DN on the Sigma; the 80mm f/2.8 Mamiya-Sekor (old style) lens set on the Mamiya TLR.

Reactions to photographs of any kind are intensely personal, and the most important and valid impressions and feelings regarding these portraits, and the entire premise of this article for that matter, are yours, not mine. However, I’ve included my own thoughts on these images in extended captions in the hope they may provide a clearer understanding of where I’m coming from. I welcome your comments and suggestions with one caveat. I know perfectly well that the camera-photographer interface is not the sole determinant of the character and content of an image, and that the correlations I’ve noted here refer to general tendencies not one-to-one correspondences.

For example, I’ve personally captured a classic New York City “street scene” that looks like it could’ve been shot with a Leica, but I actually used a tripod-mounted 8 x 10 view camera –it just happened to be set to the right distance and aperture when I swung the camera around and grabbed it. I’ve also seen many crisp, beautifully composed landscapes (including one by Ansel Adams) that were taken not with large-format view camera, but with a humble box camera. Nevertheless, I do believe that the choice of camera does affects the way the photographer makes the shot, and I sure hope you can appreciate the fascinating differences I’ve showcased here.

Thoughts on the images

Maddie, Age 11, Sigma fp with 45mm lens: Beautiful, natural, discreetly smiling expression of a “tween” coming into womanhood. It exudes joy, confidence, directness, and openness, capturing key aspects or her charming and engaging personality.

Maddie, Age 11, Mamiya C220 with 80mm lens: This more contemplative pose is far less assertive, revealing the subject’s vulnerability. It embodies the tentative, fragile quality of a pre-teen in the process of discovering and shaping her own identity, though one can also sense an underlying strength, determination, and openness to the future that presages a successful transition to womanhood. The color image is a more flattering and appealing portrait, but I think this image says more about the subject and the distinctive rendition possible with a medium format twin lens reflex film camera.

Sean, Sigma fp with 45mm lens: This is a strong and compelling portrait that conveys the sense of a person who knows who he is and stands by his convictions. However, the relatively flat, partially backlit lighting does not delineate the facial structure as well as the corresponding black & white image does. While the impression of fortitude, presence, and engagement is still evident it’s not expressed as strongly as it is in the black & white portrait.

Sean, Mamiya C220 with 80mm lens: This is a very powerful and successful portrait and the subject’s face is beautifully delineated by strongly directional widow light. The direct eye contact and calm, pleasant, determined expression convey strength of character, but also a thoughtful and sympathetic quality that is very attractive and engaging. He looks like a guy you can trust and depend on and the image also conveys a sense of self-awareness, focused intelligence, and discernment. It’s a testament to what you can do with an ancient analog TLR with close focusing ability.