grateful to have my essay on "The Stringer" online yesterday on WashPost website..here - without space limitations -- is a fuller version....I also recommend the excellent essays by André Liohn who has pierced the cloudy veil surrounding the film.

One of the main justifications for the VII Foundation film, “The Stringer”, as I heard directly from Executive Producer Gary Knight a couple of years ago, is that there needs to be truth, even uncomfortable truth, in all that we do as journalists, that we need to honor the sense of truth which journalism demands. I chose not to participate in the film, feeling that, above all else, they were trying to prove a previously chosen point of view rather than celebrate the act of discovery and enquiry. In all the decades that I have been a photojournalist, it has been a common vision that the story - the pictures, the narration - are more important than the photographer, and it is something I have always taken to heart. Yet authorship is something which cannot be easily trifled with, and we in the profession take our work seriously.

I was unaware that Gary had already decided that the question of the authorship of the “Terror of War” photograph would be worthy of a film, when he wrote me, out of the blue, in March 2023, asking if we could have a chat about my time in Vietnam, and Trang Bang in particular. Seeing no reason not to, we connected one afternoon by phone. I recall very well that I was in my car, parked in the Walgreens parking lot, and sat in the car for well over an hour, perhaps longer, as I described my time as a photographer in Vietnam (1970-72) and in particular that day in Trang Bang when the errant napalm strike led to so many civilian casualties - and from which the famous photograph emerged. No one disputes the veracity and the power of the image, and the long understood view that this picture has affected many who have seen it over the years. It is the provenance which has become the point of discussion.

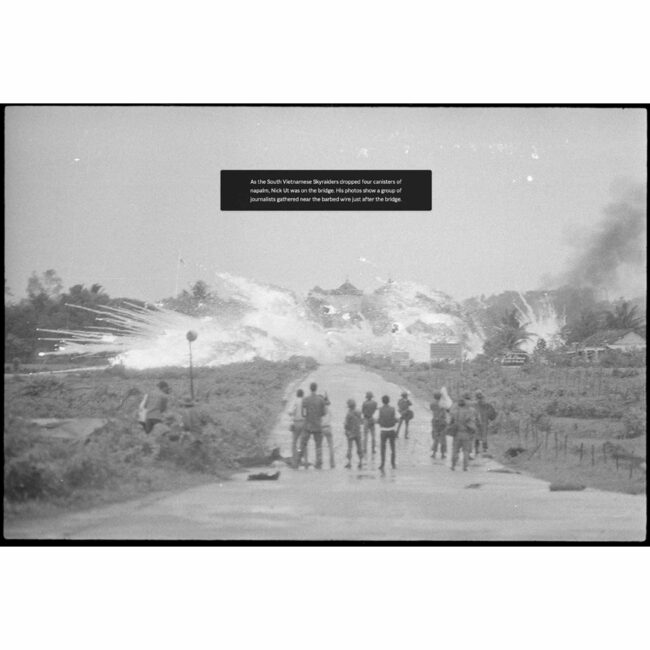

In our conversation I did mention to Gary that “as you ask around, at some point you will hear a story from a former AP photo editor - Carl Robinson - that Nick Ut didn’t take the famous picture,” a story which in my mind, really held no water. In particular I spoke of the moment which I recall with great clarity when, standing on the road outside the village, just moments after the napalm strike, with Nick Ut and freelance reporter Alex Shimkin, we saw the first of the children running through the cemetery towards the road, to escape from further danger. I was preoccupied in that moment with trying to reload my vintage Leica, the kind which were incredibly difficult to load, if you didn’t doubly trim down the film leader (which i never did.)

I know my attention was on trying to reload that camera, but what truly remains in my mind as a most powerful moment was the reaction of Nick and Alex once they first saw the victims running in the cemetery, trying to get to the road away from the fighting, and some kind of relief. Without the slightest hesitation they both began sprinting down the road, a road which at that time had virtually no journalists beyond the barrier, other than the UPI photographer stringer (Mr Hoang Van Danh ) who ended up on the right side of the uncropped famous photograph, he too, rewinding his film. But it was the initial sprint to try to get close to those running in our direction which propelled Nick and Alex, and at that moment, none of the other journalists were going down that road. In my mind, the ensuing minute or two, once the kids had arrived at the road, is when the famous picture was taken.

Then within a couple of minutes, there began a loose dissembling of the journalist group which had been lined up behind a loose row of concertina wire on the road, but all of the subsequent meandering, filming, and photographing, were definitely after the famous photograph had been taken. Did I actually see Nick photograph Kim Phuc on the road? Of course not. When you are working, you are concentrating on what you yourself see around you, making the pictures which you see, and you aren’t necessarily watching what others are doing, particularly when it is such a high pressure life & death situation as Trang Bang was. Yet, given what I remember about Nick and Alex being, by far, the first ones down the road, I believe Nick is the one who made that picture.

The return to Saigon, processing the film, etc, are stories which are well known. Carl Robinson claims that Horst told him to put Nick’s name on the caption envelope. In our world, there is a 2% chance that the absolutely wildest claims might be true, but this is one of those things which seems to me to lack veracity. I had returned to the AP bureau to have my film processed and send a couple of radiophotos to the New York Times, who happened to be my client that day. I had chosed two images, sent them to New York, and was in the photo department when the famous photograph went out. I recall vividly that once back in the office from lunch, and the picture had been printed, and was being wired out to the world, Horst did congratulate Nick in a very Horst-like way, with his unmistakeable accent saying “You do good work today, Nick Ut.” That is word for word what he said.

But back to my interaction with Gary Knight some fifty years after that day in Trang Bang. From our phone call, I appreciated that he wanted to know about what i knew, what I had seen, and in what I would attribute to a gesture of professional courtesy, I sent Gary a dozen of my b/w pictures from that day, in an effort to perhaps fill in a little of the way it all looked. There was no intention other than to share my story, and what I’d seen, with a fellow photographer and certainly at that time, no idea of a documentary film. And no mention of a film was made to me or that my photos would be exploited and even worse, used without crediting me in the film, which goes against both the ethos of professional photojournalists and violates the law.

In January 2024 I received an email request from Fiona Turner, one of The Stringer’s producers and Gary’s wife, asking me to confirm authorship of a number of b/w images - the ones i had sent Gary a year before - which I did. She then asked who (myself, or my agency, Contact Press Images) would be the appropriate one to license images for the film. I replied by email on 1/16/24 “Thanks for your note... as far as i can tell those are my images, but Im not comfortable licensing any of my Vietnam images for this purpose at this time.” By contrast, when the AP decided to do their own follow-up investigation, I did license a number of images which they used in their report.

It could not have been more clear that I did not wish to license the images for the film. Other than a couple of subsequent phone calls with Gary, asking me to be interviewed for the film, that was the end of my brief interactions with the production team. Having already seen what their purpose was - to try to prove that another photographer had taken the famous photograph, I was torn about doing an interview, but in situations like this, you have zero control, zero input as to how what you say might be edited, and cut, and I wasn’t confident that my point of view would honestly be represented.

So when I finally watched the film this week on Netflix, I was astonished and crestfallen to see something like ten of my pictures used in the film’s narration, all without attribution, and in direct contravention of what I had written Fiona. And it wasn’t as if they couldn’t have known they were my photographs. During one of the panning shots of the production team working on a large white board, trying to track the time and place movements of the principals, one of my pictures is stuck on a lower left corner of a panel with a blue post-it note on which is written “DB” - obviously one of my images. Additionally, they used a clip from a video interview I did with Robert Caplin at Adorama, also without any attribution, all of which might have falsely given the impression I was collaborating with the filmmakers.

More than anything I feel like this film is less a documentary and more of an unfairly constructed, and carefully assembled polemic, with historical elements altered to meet their desired conclusion. The fact that my pictures were dropped into the film, after I refused, is a grievous miscarriage of justice, and copyright infringement. Is that the kind of “truth” and honesty that Gary and his team deployed for other elements of the film? There is a deliberate disingenuousness and deception which remains at the forefront. I sent the pictures to Gary, prior to any knowledge of there even being a film, as an act of one friend in the business, to another. Other than a couple of phone calls asking me to sit for an interview, I never heard back from Gary. Neither was there an offer before or since the Sundance festival to view a screener. Gary never mentioned using my pictures in the few times we had further short conversations. This kind of betrayal makes you think twice the next time a colleague calls to ask a question about a place or to see images of where you might have worked.

I still believe that while the film tries to prove that “Nick Ut couldn’t have taken the picture…” in my mind, Nick Ut, having been the first and only photographer to run down the road towards the pagoda and the oncoming children, was the only one who COULD have taken the picture. Mr Nghe, the “stringer” appears in several of my photographs. He has his camera, yet, like the NBC crew he was accompanying, he didn’t come down the road to where the children were until the dispersing movement of the group of journalists.

He certainly wasn’t all alone, down the road, in a place to have made the picture. I am one of maybe five people still alive from the road that day - yet little deference is given to the word of actual eyewitnesses over digital recreations. We are, of course hemmed in fifty years later by the existing media from that day, none of which was “time coded” and thus providing choppy and incomplete versions of what happened, and when. But some things live on as memories - strong memories - and for me, some of the memories of that day in Trang Bang feel like yesterday.

David Burnett Dec. 11 2025

one of my photographs used in the film, of Kim Phuc's sister, and to the right, Nick Ut, at work...a terrible day in Trang Bang